“We apologize, but due to Ebola virus we are not accepting Africans at the moment.”

This is what a bar in Itaewon, a popular area for expats and tourists in Seoul, publicly posted in front of its property last month.

The statement triggered thousands of angry comments online, both from expats and locals ― especially after the public learned of reports that the bar admitted a white person from South Africa, while banning almost all dark-skinned individuals, regardless of their nationalities.

The incident is likely to get attention from Mutuma Ruteere, the U.N. special rapporteur on racism. Ruteere is scheduled to visit Seoul later this month to monitor the situation of racial discrimination and xenophobia in Korea and will file a report to the U.N. Human Rights Council next year.

The incident is one of the growing number of racism cases in the country ― Asia’s fourth-biggest economy, a key manufacturing powerhouse in the region, as well as the producer of hallyu.

While the nation’s immigrant population continues to rise, Korean racism ― both structural and internalized ― is becoming a growing concern to the international community.

Complex nature of racism in KoreaKorean racism, however, must be understood differently from its Western cousin, experts say.

It is a complex product of the country’s colonial history, postwar American influence and military presence, rapid economic development as well as patriotism that takes a special pride in its “ethnic homogeneity,” according to professor Kim Hyun-mee from Yonsei University.

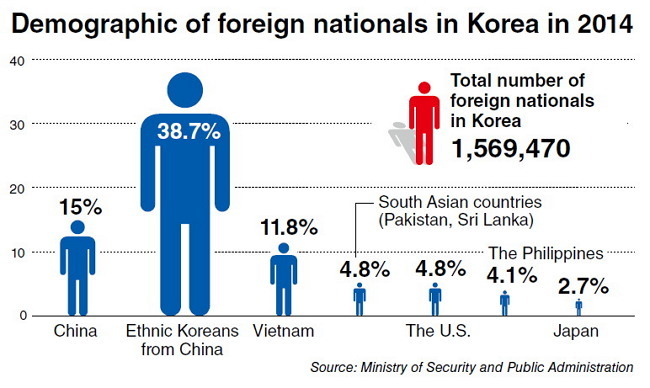

Unlike racism in the West, Korean racism is mostly targeted against those from other Asian nations, she noted. As of this year, more than 80 percent of immigrants residing in South Korea are from countries in Asia, the largest number coming from China and Vietnam.

“After the country survived the poverty (after the war) and became a member of the OECD, Korea has been celebrating its own success,” Kim said in an interview with The Korea Herald.

“One of the most serious side effects of the country’s rapid economic development is that its people started to hierarchize foreign nations according to their economic status. Collectively, they would perceive specific nations, mostly developed countries such as the U.S. and the U.K., as their superiors whom they should learn from ― just think about how obsessed Korea is with English language education ― while perceive economically developing countries as their inferiors with no specific grounds.”

Prejudices against those from less developed countries often go to the extreme. For instance, in 2011, a woman from Uzbekistan was reportedly denied entry to a public bathhouse in Busan, despite showing her South Korean passport, as the owner of the property was concerned that other patrons may “contract AIDS” from her.

Korean racism also contains internalized white supremacy, Kim added. “After the Korean War, Korea became a country with U.S. military presence. At the same time, it was exposed to American popular culture, including Hollywood films, and was influenced by their representation of visible minorities,” Kim said.

“We need to note that interracial marriage was legally banned in (parts of) the U.S. until 1967. The very first children who were sent overseas for foreign adoption in 1954 from Korea were mixed-race children born to African-American soldiers and Korean women.”

Internalized white supremacy can be seen even in today’s TV shows in Korea, according to a local NGO Women Migrants Human Rights Center of Korea.

When a Korean person is married to a (white) citizen of Western country, his or her family is referred as a “global family” with a positive connotation by hosts on TV programs, while families consisting of a Korean man married to a woman from a Southeast Asian country is called a “multicultural family,” a term that is rather stigmatizing and discriminatory among Koreans, the NGO wrote in a report to be submitted to U.N. Rapporteur Ruteere.

Racially insensitive programming on Korea’s national broadcasting networks have also emerged as a problem. In February, national broadcaster KBS aired three Korean comedians, dressed as “Africans” by wearing a curly wig and painting their faces black, in a segment in its comedy show “Gag Concert.” The program received a criticism from expats here, saying that it was racist and extremely inappropriate.

Discriminatory policy

Korea also has a discriminatory policy against those who wish to immigrate to the country from specific countries, including China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Cambodia, Mongolia, Uzbekistan and Thailand, the NGO noted. Only citizens from the seven particular countries must complete a special educational program on international marriages in order to obtain the F-6 visa, a visa given to foreign spouses who married Korean nationals.

“The government says it is because citizens from these specific countries move to Korea by marrying Koreans the most,” Han Gook-yum from the NGO said in a racism-related forum in Seoul last month. “But Korea also gets a large number of people from the U.S. and Japan, who move to the country by marrying Korean nationals.”

According to government data, the third-largest number of immigrants who arrived in Korea after marrying Korean nationals in 2011 were from Japan, while the number of American spouses of Koreans exceeded the ones from Uzbekistan in the same year. More than 85 percent of the marriage migrants in Korea are female.

As of this year, there are more than 1.57 million people from overseas in Korea, most of them from Asia, including foreign brides and international students. That accounts for more than 3 percent of the entire population in the country.

Among them, the largest group ― 34.3 percent ― are people who moved to Korea for work.

“Many Koreans say migrant workers ‘volunteered’ to come to Korea, and they should move back to their countries if they don’t like it here,” said a human rights activist who wanted to remain anonymous. “But you have to understand that for many of them, marrying a foreign national or working overseas may have been the only option to survive financially.”

While most expats from developed nations, such as language teachers, have the option of going back home, she said, those from developing countries often do not have such an option, largely because they lack financial means and opportunities. “This makes them more vulnerable to all sorts of abuse in Korea, including racial discrimination and exploitation,” she said.

Misguided multiculturalism In April, a study by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies noted that most of Korea’s “multicultural” policies and programs targeting immigrants, such as educational classes on Korean manners and customs, have been aimed at cultural assimilation, while the term “multiculturalism” originally referred to the act of respecting different cultures and ethnicities.

Local activists also point out that many Korean organizations reward migrant wives who they consider as “dutiful, devoted daughter-in-laws,” as a way to assimilate them into Korea’s traditional and patriarchal culture ― especially in the country’s remote and rural areas.

For example, a young migrant wife from Vietnam living in a Korean farm village was awarded the “devoted daughter-in-law award” from a local NGO in 2009. The 29-year-old received the prize for taking care of her intellectually disabled Korean husband, nursing her ill parents-in-laws, as well as her grandmother-in-law, on top of doing farm work and domestic labor all at the same time.

“(Such awards) show Korean society’s pressure on migrant women, that they should diligently fulfill their duties as daughters-in-law in Korea’s male-oriented families, in spite of them being ‘foreigners,’” the Women Migrants Human Rights Center of Korea wrote in its report.

“But these pressures are only put on women from developing Asian countries. (No Korean) would have the same expectation of white women from Western countries.”

Racism in English education

On top of migrant wives and those who work in factories, farms and fishing industry, cases of racism have been reported frequently in the country’s education sector as well. Nonwhite native English speakers, such as African-Americans and Asian-Australians, have been denied English-language teaching jobs here, in spite of their language skills for simply “not being white.”

In 2009, Bonojit Hussein, an Indian national who was serving as a visiting professor at Korea’s Sungkonghoe University at the time, was called a “dirty, black foreigner” in public by a Korean man while riding a bus in Bucheon, Gyeonggi Province. The attacker, who told Hussein to “go back to his country,” also attacked his companion, who was a Korean woman, by shouting, “Does it make you feel good to date a black person as a Korean woman?”

Professor Kim from Yonsei University said the problems stemming from racism has to do with the country’s rapid modernization in recent decades. “Korea has accomplished both democratization, economic and cultural development all at the same time in a short period of time.” Kim said.

“At this point, though, we need a serious soul-searching on where do we go from here. For example, because of hallyu, these (problematic) comedy shows are being watched by overseas viewers now.”

The underlying perception behind racism and prejudice against foreigners is linked to the country’s ethnic homogeneity, but Kim said the notion was largely a myth.

Myth of ethnic homogeneityMarriages between Korean men and Japanese women were common during the Japanese colonial period, while many women during Korea’s Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) were forcefully taken to today’s Mongolia, as the Korean kingdom was often invaded by the Mongolians.

One of the most significant victims of such Korean notion of ethnic homogeneity and “pure blood” nationalism is some 220,000 Korean children sent overseas for foreign adoption throughout the past six decades, Kim added.

“The children of Korean-Japanese couples (during the colonial period) didn’t look very much different from Korean children. But children of American soldiers and Korean women were considered a threat to Korea’s ethnic homogeneity, because they looked distinctively different from the rest of the population. One of the very first legislations that the Syngman Rhee administration introduced in 1954 was the bill that allowed the government to send children away for adoption without the approval of the foster carers.”

The key to combating racism in Korea is to introduce public education that encourages to respect different cultures and ethnicities, activists said.

“Victims (of racism) educate themselves about the concept of discrimination and intolerance, and they often learn by their experiences. But the general public, especially those who belong to the mainstream, often do not get that education,” said Emile Kim, a former pastor and anti-racism activist who spent more than 20 years in the U.S.

“It is equally important to educate the general Korean public about other cultures and the concept of tolerance (as much as it is to educate immigrants).”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com).