In March 2015, a 14-year-old girl was found dead lying on a bed in a motel in Gwanak-gu, southwestern Seoul.

The victim was identified as a runaway teenager. Not long after leaving home in November 2014, she met three pimps and began selling sex through smartphone apps. The girl was strangled by a 38-year-old male customer, who then fled the scene. The perpetrator admitted to the crime, saying he felt she was not worth the money.

The horrible murder shocked the public.

But Cho Jin-kyeong, the executive director of Stand Up Against Sex-Trafficking of Minors -- Teens Up for short -- said such nightmares are still ongoing for many teenagers in South Korea.

The nonprofit group supports victims of underage prostitution by offering counseling services, legal and medical support and rehabilitation programs. The group also monitors online pimping sites, works to get new legislation introduced, and promotes public awareness of the issue.

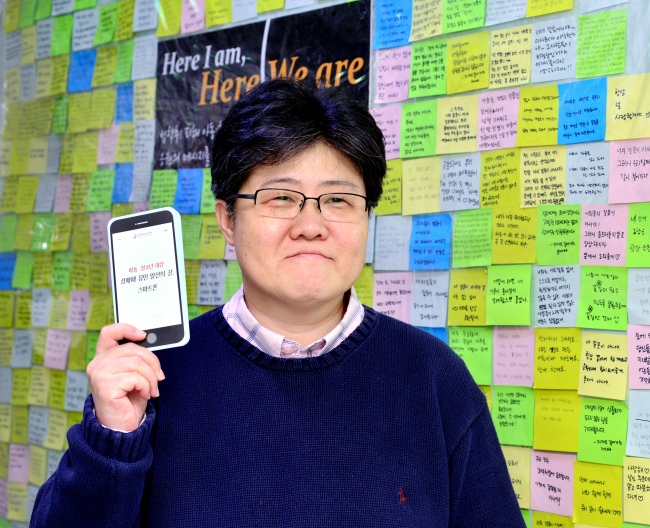

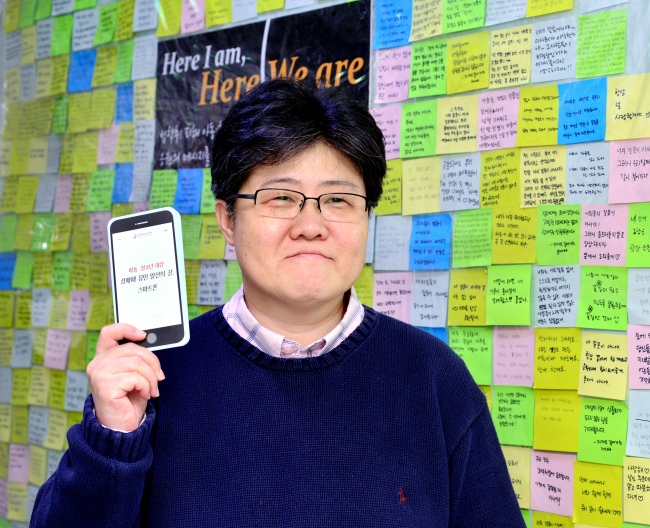

Cho Jin-kyeong holds up a Teens Up in front of a wall in her office full of messages of support for victims of underage prostitution. (Park Hyun-koo / The Korea Herald)

Cho, who has been assisting sex-trade victims for the past 19 years, established the group in 2012 to help minors after learning that many adults in the sex trade got started as teenagers.

“As the years pass, the problem of underage sex trafficking is getting far more serious than we expected,” Cho told The Korea Herald.

The fast-developing online social networking platforms are at the center of the problem, Cho explained.

Changing patternsAccording to Cho, before 2000 teenagers could be spotted working at adult entertainment establishments such as brothels and hostess bars, in the absence of specific laws to protect them.

When the Act on the Protection of Children and Youth against Sex Offenses was enacted in 2000, minors were forced out of the business.

“Many of the teenagers involved in the sex industry didn’t have any place to return, as most of them had escaped from homes where their parents had abused them physically or sexually. The law just drove the kids out from the business, rather than considering the root causes as to why the kids were working in such facilities,” Cho said.

As the internet took off in early 2000, teenagers began to be exposed to online chatting websites. Adults they met on chatting sites lured them to work at so-called “ticket cafes,” which send teenagers to deliver coffee to customers’ homes and provide sex.

“As teenage servers working at the ticket cafes became a serious problem, the government banned the ticket cafe owners from hiring minors. Then where do the kids go?”

Also, as the online sites began to evolve into for-pay chatting services around 2014, teenagers who could not afford the fees left the platforms.

(123rf)

Underage sex trafficking then moved to the world of mobile phone chatting applications. The applications, which enable people to meet random strangers, have emerged as the perfect method to connect teenagers with sex buyers, Cho said.

“There are many online communities of runaway teenagers. Through such websites, pimps recruit teenagers and get them into sex trafficking, moving them from place to place.”

Cho said the pimps frequently use mobile chatting apps to find potential sex buyers, pretending to be minors themselves. Some teenagers are connected directly to the sex buyers through apps.

In a 2016 Ministry of Gender Equality and Welfare survey of teenagers who had experienced sex trafficking, 60.8 percent of the respondents said they had met the buyers through mobile chatting applications.

“It’s easy to deceive others on the apps, as they don’t require the users to go through any verification process,” Cho said.

When asked what the process was like, Cho recommended that the reporter download one of the random-chatting applications on the phone and try it during the interview.

“Just set your age at whatever you want -- they won’t check it at all anyway. Set your username to include ‘choding’ (meaning an elementary school student in Korean slang), which implies that you are a kid,” Cho said.

As soon as the reporter started the application with the username “Choding excited over the spring breeze,” four men messaged simultaneously, saying, “Your username is cute,” “How old are you?”

A few minutes later, another person sent messages that said, “Let’s meet and I’ll pay you.” Another message read, “Are you interested in a part-time job that pays you 50,000 won ($44) per hour?”

Director Cho speaks in an interview with The Korea Herald in Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo / The Korea Herald)

“There were five applications that were popular as sex-trafficking platforms in 2014. The biggest problem of the services is that they allow the users to be anonymous, without verifying their age or identity.”

Since their launch in 2014, these apps have been called a breeding ground for underage sex trafficking.

“The applications allow people to check off their ages on their own. That way, they can blame the users (for lying about their ages) and avoid their responsibilities to ban minors from using the platforms.”

Cho added that some applications even offered services that help users transfer money.

In 2016, Teens Up sued the developers of seven applications for alleged brokering of sex trafficking, but the accusations were dismissed on the grounds that the applications did not intend for the users to abuse the platforms and that the government has been monitoring the applications.

The Gender Ministry said it had found 53 people who used the applications for sex trafficking in 2017, 60 in 2018 and 20 between January and March this year.

The actual number of people would be much more than what the ministry found, Cho said.

Victims of underage sex trafficking

According to Cho, underage sex trafficking is no longer just an issue for runaway teenagers.

“Sex trafficking has now become ‘normalized’ among young kids, no matter whether they are attending school or living with their families. The ages when the kids are first exposed to such crimes are getting younger as well.”

Cho said Teens Up received calls from three mothers of elementary school students one week in December 2018. They were worried about their kids, who had sent inappropriate photos to unknown adults via mobile chatting applications.

Since July 2015, the number of students in Teens Up’s training program for sex trade victims has surpassed the number of teenagers in the program who have dropped out of school, Cho said.

“The reasons why the teenagers get involved in sex trafficking vary case by case. Some students start to chat with random people out of curiosity and become close with them by talking about the pressure of studying or complaining about their parents.

“When the other person asks them to send illicit pictures of their bodies, some students actually comply with the request because they are afraid to lose the person. Once they send it, they can easily be threatened by the adults who say they will distribute the photo if the kid does not get involved in the sex trade. Such actions are called grooming, which can be commonly found online.”

Even though each situation is different, all minors engaged in the sex trade should be considered crime victims, Cho said.

“No kid is born for sex trafficking. Every victim has the first moment (when the person gets involved in the sex trade), and the moment is always exploitative in all cases. At every step of the sex trade, there is no one to take care of them.

“Our society often blames the minors for getting involved in sex trafficking, which makes the matter worse. Some teenagers get no support even from their parents, who point to their child as being ‘problematic’ or ‘obsessed with sex.’”

Cho Jin-kyeong talks about the sex trafficking of minors in Korea at the Teens Up office in Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo / The Korea Herald)

In the same context, investigations of underage sex-trafficking cases should not label the victims as accomplices or as people who willingly took part in the sex trade, Cho claimed.

“When I go to the trials, I see many sex buyers defending themselves by telling the judges how committed they are to their families or how impoverished they are. But I’ve never seen anyone ask … such things of teenagers.

“It’s important to consider what drove the teenagers to prostitution, rather than focusing on why they did it , before dividing them into victims of and participants in the sex trade.”

Under the current law, minors who engage in prostitution can be sent to centers for the protection and rehabilitation of juveniles.

Once those minors are confirmed to have been involved in prostitution, it becomes extremely hard for them to get any support from the government, including help from government-appointed lawyers or women’s help centers, even though they have experienced sexual violence.

According to a 2016 study conducted by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, about 80 percent of 103 teenagers who engaged in sex trafficking said they had faced unfair situations during prostitution, such as the man not wearing condoms or not paying the amount that was promised. Some experienced death threats or were raped.

But it’s not easy to report such incidents to police because they are afraid of being accused of engaging in the sex trade.

A solution to the problem of underage sex trafficking is to make adult sex buyers take full responsibility, Cho said.

“The law should be changed to punish the adult sex buyers only. When the adults are given severe punishment, they will no longer approach minors for prostitution. Even if the sex buyers want to do it, they will ask girls for their age.

“When a 15-year-old boy gets caught buying cigarettes, the law punishes the seller. But when a 14-year-old girl is caught for engaging in the sex trade, the law makes the girl responsible. Isn’t it absurd?

“The offenders tend to attack minors even more terribly compared with adult victims, as they are weak and often don’t have protectors to save them. Horrific cases have emerged every year, including the Gwanak-gu murder, but I’ve been surprised by people’s insensitivity to the problem. As of 2019, it’s now an extremely serious problem in Korea.”

(

jupark@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] How DDP emerged as an icon of Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050915_0.jpg&u=)