When Kim Young-mi, a 63-year-old housewife in Seoul, held a group prayer meeting at a catholic church in her neighborhood last week, the economic situation was at the top of her prayer list.

“I am deeply concerned about the future of the nation’s economy,” Kim said.

As an ordinary citizen, Kim said she has yet to directly feel the economic pinch, but she has been growing more concerned by the flurry of news reports warning of the looming economic crisis.

What was most distressing to Kim and other Koreans were the series of recall debacles involving two major conglomerates, Samsung and Hyundai Motor, who as major exporters pulled the country through an economic crisis from 1997-1998.

“Samsung and Hyundai are the two big vehicles that have led South Korea’s economy. But with them reeling from such negative events, we are worried.”

For Kim Min-sun, a 36-year-old office worker in Seoul, Samsung and Hyundai have been a source of pride.

“My foreign friends didn’t know where Korea was, but they knew Samsung and Hyundai, telling me what fascinating products they make,” she said.

The two corporations have been driving Asia’s fourth-largest economy for decades, with their combined sales accounting for 20 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. Their market value hovers at around 250 trillion won ($217 billion).

Samsung Electronics, the world’s largest smartphone and chipmaker, makes up 29 percent of the nation’s export revenue, according to recent data from the Korea International Trade Association.

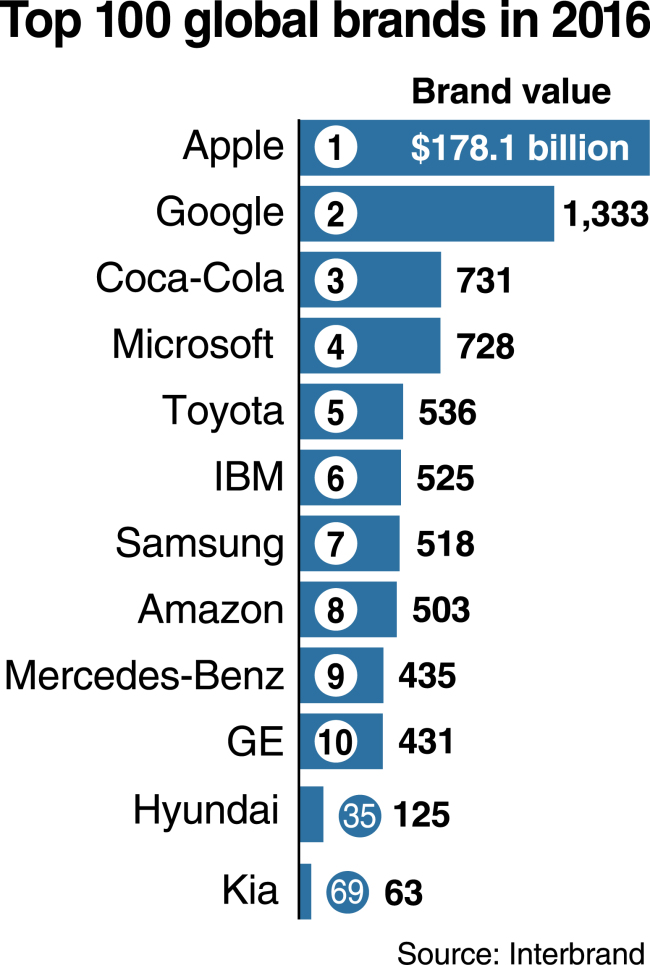

Samsung and Hyundai are also among the top 100 brands in the world, with the tech giant’s brand value at $51.8 billion and Hyundai at $12.5 billion.

The sense of fear on the fate of the nation’s economy is spreading fast. Many say the current situation of South Korean firms struggling amid a political crisis seems to hark back to the bitter memory of the economic crisis 20 years ago, when the nation was forced to take a tough bailout package from the International Monetary Fund as a scandal plagued then-President Kim Young-sam.

Indicators of the nations health are pointing to trouble ahead, too.

The nation’s central bank last week lowered its economic growth forecast from 2.9 percent to 2.8 percent. The growth rate of the manufacturing sector hit a 7 1/2-year low of minus 1 percent in the third quarter, the bank said.

“The signs of industries struggling are likely to show up more clearly starting next year,” said professor Chun Seong-in of Hongik University in Seoul.

“I am quite pessimistic (on the outlook of industries) particularly if the void of government continues with more than a year left for (President Park Geun-hye) in office,” he said, referring to the economic ramifications of the recent political scandal involving the president’s friend Choi Sun-sil.

Samsung has been in hot water after successive cases of its high-end smartphone Galaxy Note 7 catching fire. Though the tech giant moved fast to recall millions of the phablets around the world, the market raised concerns over the company losing money and its brand value. Some suggested that the crisis has exposed a loophole in the conglomerate’s business operation and management.

The performance of Hyundai Motor Group, the nation’s top automaker, has also been dwindling, in the face of global recalls and labor disputes.

In late September, the South Korean carmaker was found to have settled a class-action lawsuit over the Sonata’s Theta II engine in 885,000 vehicles manufactured between 2011 and 2014. In addition to its tarnished image, the carmaker came under fire for treating local customers differently from those overseas.

The outlook remains grim for Hyundai, according to local analysts, who say that it will be difficult for the carmaker to achieve its goal of selling more than 8 million units this year. Its third-quarter net profit also dropped 7.2 percent to 1.12 trillion won, in the third quarter from the same period last year, the company said in a regulatory filing last week.

Korean steelmakers and shipbuilders, once praised as pillars of Korean exports, are also struggling.

The country’s top steelmaker Posco faced a sharp fall in its sales, which reached 550 billion won in 2014 in the aftermath of the collapse of the shipbuilding industry and steel oversupply from the Chinese market. It recorded a net loss of 96 billion won last year for the first time in 47 years. The anti-dumping duties imposed on it by the US and India earlier this year posed more challenges to the company.

With aggressive restructuring efforts and cost-saving measures, however, the steelmaker saw a 52.4 percent rise in its operating profit, which reached 1.3 trillion won in the third quarter of this year, exceeding 1 trillion won for the first time in four years. Its net profit also surged by 115.6 percent to reach 475 billion won.

The sales increase of its overseas subsidiaries and high value products such as World Premium, and the rise of Chinese steel prices -- prompted by large-scale restructuring there -- contributed to Posco’s performance improvement, the company, said.

Amid the lack of ship orders caused by low oil prices, Hyundai Heavy Industries and Samsung Heavy Industries have sought restructuring measures such as job cuts, asset sales and efficiency improvements.

Although the operating profits of both firms remain in the black while they speed up restructuring, challenges remain, as their order rates are still far short of their goals. Hyundai only reached 22.5 percent of its order goal, while Samsung had achieved only 15 percent as of late last month.

The biggest concern in the shipbuilding industry is Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering, which still suffers from the aftermath of an alleged 5 trillion won accounting fraud and liquidity woes prompted by a delayed ship delivery, despite a massive injection from the government.

As of last month, the amount of orders that the company obtained remains at $1.3 billion this year, far short of its initial worst-case goal of $3.5 billion.

It is true that the Korean companies are in worse shape than before, says Mun Byung-ki, a senior researcher at the department of analysis and forecast at KITA.

But the characteristics and extent of their troubles are a lot different from those businesses experienced during the Asian currency crisis.

“Things are different from the past. Korea is unlikely to go through a currency crisis, as the nation’s trade surplus is hitting a new record high every month,” he said.

“The theories of the economic crisis (sparked by businesses losing growth momentum) appear to prevail as the businesses are in a transitional process toward new industries,” he said.

Businesses are in a paradigm shift, Mun said, citing the example of carmakers betting on electric vehicles and tech companies leaning more toward software.

Kang Joong-ku, a researcher at the LG Economic Institute, also said that the industrial structure worldwide is undergoing a major transformation with the service sector slowly replacing the dominance of the manufacturing sector.

“The manufacturing sector already entered a phase of stagnation two or three years ago. It is difficult to expand export volume by relying on manufactured goods anymore,” said Kang.

The government admits the need to nurture new industries, citing China’s fast growth in the manufacturing sector, which is pressuring Korean firms to shift their focus to value-added, high-tech industries.

The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, plans to unveil new measures to nurture new industries in December.

The list is likely to include artificial intelligence, electric vehicles and the Internet of Things. The amount of financial support to be made available remains undisclosed.

“Eventually, it is the companies that mull on future industries over the most,” said Joo Hyung-hwan, the minister of trade.

“Policies on industries will be about lifting regulations on sectors that private companies are willing to lead.”

By Cho Chung-un (christory@heraldcorp.com) and Lee Hyun-jeong(

rene@heraldcorp.com)

The Korea Herald is publishing a series of articles on the alarming state of the country’s economy and the challenges to be addressed. This is the second installment -- Ed.