Director and young performing artist delve into the world of Korea’s indigenous spirituality Aside from the comical talk-show character “The Knee-Drop Guru,” and a few TV drama shows such as MBC’s 2004 flick “Lotus Flower Fairy,” it’s hard to come across much about Korean shamanism in popular culture.

In the contemporary art scene, however, two artists have recently come up with unconventional works that shed light on the historical and artistic value of shamanism.

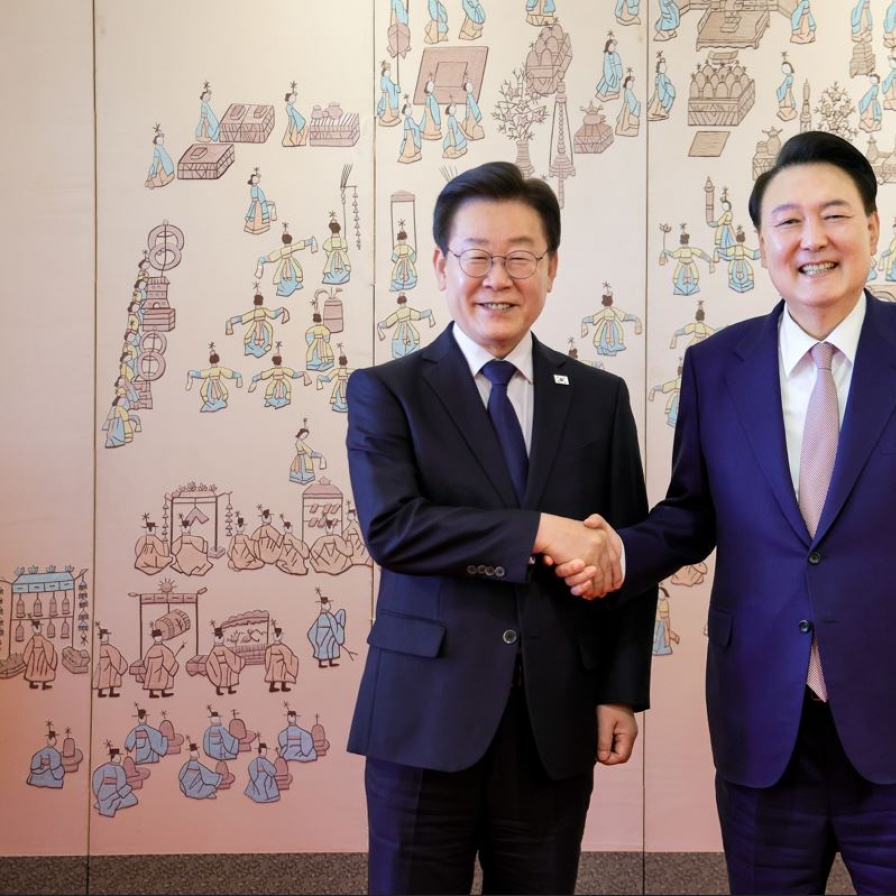

Park Chan-kyong (Ahn Hoon/The Korea Herald)

One is media artist Park Chan-kyong, who last year won the Golden Bear prize at Berlinale for his film “Night Fishing” shot with an iPhone.

The short film, which he directed with his director brother Park Chan-wook, reflected his long-time interest in Korean shamanism ― exploring the theme of life and death while providing a rare glimpse into the traditional practice.

He is developing another film about Korea’s indigenous spirituality this month, a non-fiction piece about female shaman Kim Kuem-hwa.

“I’ve always been interested in shamanism, ever since I was a kid,” he told The Korea Herald at his office in Seoul.

“I’ve never seen a ghost in my life. But I’d always imagine them and been scared of them. It’s always good to believe that there’s an unknown world out there, which you will never be able to fully understand. It humbles me.”

A scene from director and media artist Park Chan-kyong’s upcoming fantasy documentary “Crossroads” (Festival Bo:m)

The film, titled “Crossroads,” belongs to the “Asian Gothic” genre, a term which Park coined. It features the life of Kim, who is a Korean intangible cultural heritage, mixed with her flashbacks of the Korean War which are performed by actors and actresses.

“When I say gothic, I am talking about the movement in the 19th century Europe,” Park said. “It includes dark, horror and fantasy literature, such as the works of Poe and romantic paintings by J.M.W. Turner. There was a great yearning for a change, fantasy, foreign culture and break-away from what they already knew.

“I think the ‘gothic’ movement took place in Asia in a different way. We no longer find Western culture as something shocking and foreign. Instead, we find our own traditional culture very foreign and shocking.”

Kim Seong-hee, director of Festival Bo:m ― Seoul’s international multi-disciplinary art festival where Park’s film will be screened later this month ― said there’s a growing trend in both the arts and academia that seeks to examine the past to better understand the present and the future.

The two works featuring Korean shamanism, which will be featured during the festival, are an example of that, she said.

“The 20th century was all about science, logic and technology,” Kim told The Korea Herald.

“But we’ve seen the limitations of that approach to understanding our existence. So the new trend is to go back to our ancient myths, imaginations and fantasies.

“More scholars and artists are looking into the things that used to matter to us, but are considered outdated and ‘unscientific’ today.”

The life of Kim Keum-hwa, the leading character in Park’s film, encapsulates exactly that. Born in 1931 in a rural town in Hwanghae Province, now in North Korea, Kim became a shaman at the age of 17. She was said to be a prolific dancer and singer, perfect for Korea’s shamanic ritual performance “gut.”

Korea’s traditional shamanic service, “gut,” taking place in Seoul (Suh Yeong-ran)

Her life as a shaman has been deeply linked with Korea’s modern history, as well as its wounds. During the Korean War, Kim was often threatened with death by both South and North Korean soldiers, accused of deceiving people with her practices.

During the 1970s, she and other shamans were oppressed by Park Chung-hee’s authoritarian government and their “New Community Movement.” The political initiative, which was launched to modernize the rural economy in Korea, included an agenda to get rid of the traditional shaman customs, calling it “superstitious” and “unscientific.”

“It’s a shame,” Park said. “Korea’s Protestant church, on the other hand, expanded its influence by absorbing the local shamanic customs, such as early morning prayers. I think the church has been very eager to denounce shamanism because of the similarities they share, not the differences.

“I found ‘The Knee-drop Guru’ disturbing because the making of such a caricatured representation of shamans doesn’t pay any respect to the traditions they carry in real life,” he continued. “On the other hand, having such caricatures of priests would be just unthinkable in today’s TV shows.”

In the movie, Kim’s flashbacks of her past intersect with her present day “gut,” shamanic service, which took place in the hillside cemetery in Paju, Gyeonggi Province ― where Communist warriors were buried after the war. The site is commonly called the “enemy cemetery” by the locals.

The shaman’s service was to console the spirits of the deceased soldiers buried at the site.

“The question is, can politics and the ideological dispute really mean anything when a vast number of innocent lives are lost,” Park said.

“In such situations, what matters is forgiveness and reconciliation. I think shamans and their service ‘gut’ made that possible for the Korean people. It brings reconciliation between the dead and the living, releasing the resentful emotions from the past. Kim reconciled with her own past through her service as well, with the ones who had threatened her to kill her with guns during the war.”

Meanwhile, young performing artist Suh Yeong-ran takes a different approach to Korean shamanism. The 28-year old majored in dance at university, and was fascinated when she discovered a lot of contemporary dance moves have their roots in ancient religious rites and rituals.

A meal prepared for a “maeulgut” in Seoul, a shamanic service wishing for a village’s good fortune (Suh Yeong-ran)

“When I heard about that, I thought, well, Korea has its own tradition in religious rituals,” Suh told The Korea Herald. “So last year I started a year-long study on Seoul’s ‘maeulgut,’ shamanic services wishing for each village’s good fortune, and videotaped their rituals and customs.”

Through her research, Suh met many maeulgut practitioners in Seoul, who are mostly in their 50s and 60s.

“The whole process was extremely interesting,” Suh said. “One of them genuinely believed that his town has never had a flood because of their maeulgut service.

“At the same time, many were reluctant to share their views, saying ‘someone so young like you would think we are weird for doing this.’ But the practices turned out to be very convincing in many ways.”

In her multi-disciplinary art work, titled “I Confess My Faith,” Suh mixes the video footage with her own dance performance inspired by the shamanic rituals.

The piece, which will also be featured at Festival Bo:m, links the folk custom to her own interpretation of performing arts, offering a rare artistic experience to her viewers. Suh found the ritual body movements intuitive and natural, unlike contemporary dance which sometimes requires contrived movements.

“Korean ‘gut’ can be totally seen as a form of performing arts,” director Kim said while explaining Suh’s piece. “In fact, it’s perfect to be called that.”

Meanwhile, Park said he wanted the film “Crossroads” to be seen as a ”gut“ service.

“I was particularly intrigued by shaman Kim’s earlier years in her rural home town,” he said.

“Just imagine living in a remote town in the 1930s where there is absolutely no means of entertainment and medical doctors.

”How fascinating it would have been for you to watch a female shaman, dressed in colorful costume, singing and dancing on knives? Who would you speak to when your children got sick? Shamans were both entertainers and caregivers when we did not have much.”

A segment of “Crossroads,” will be screened on March 24 and 25 at Baik-Chang Theater of the National Theater Company of Korea in Seoul, while Suh’s “I Confess My Faith” will be performed on March 31 and April 1 at the National Theater Company of Korea’s Pan Theater. For tickets and information, call (02) 730-9616 or visit www.festivalbom.org.

By Claire Lee (

dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[Grace Kao] Hybe vs. Ador: Inspiration, imitation and plagiarism](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050220_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Mom’s Touch seeks to replicate success in Japan](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050568_0.jpg&u=)