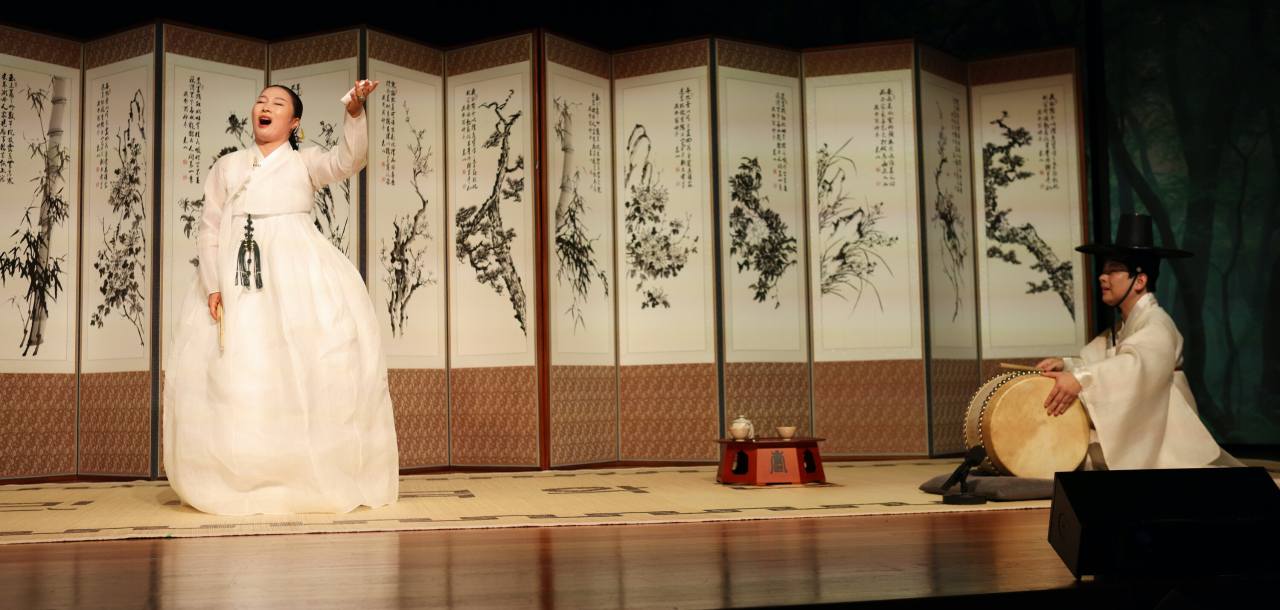

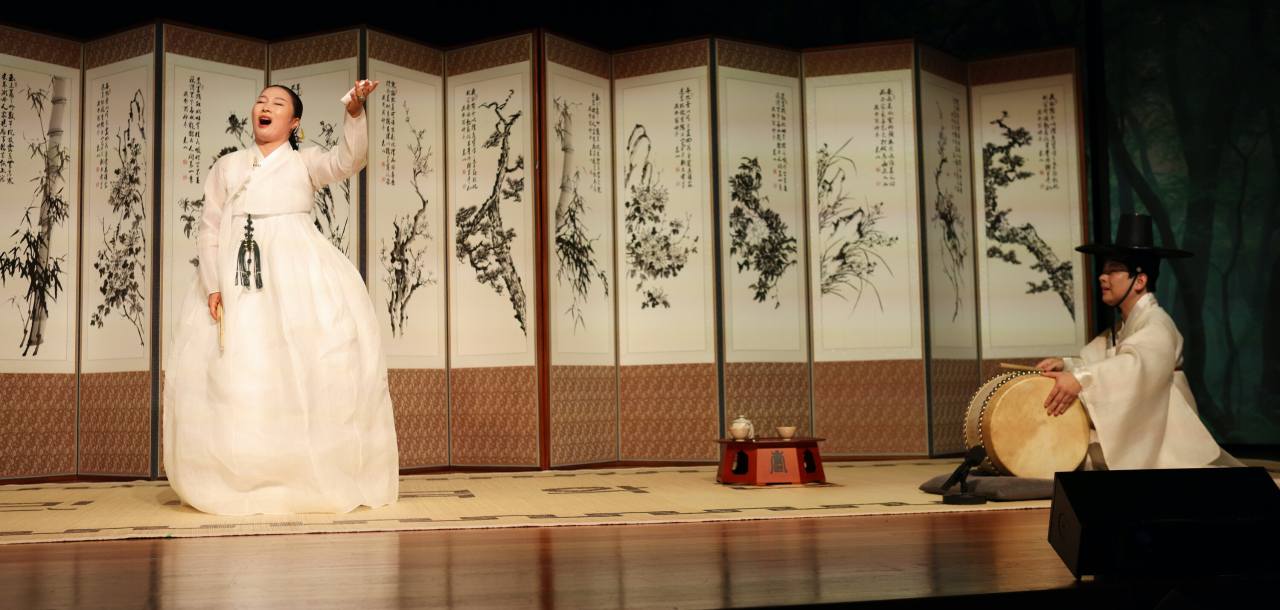

Pansori myeongchang Heo Ae-sun performs “Simcheongga” with drummer Go Jeong-hoon at the Namwon Public Library in Namwon, North Jeolla Province, Korea, Photo © Hyungwon Kang

Among Korea’s oral traditions, “pansori,” or narrative singing of epic stories and folklore drama, is performed with audience participation.

A solo performer who sings and narrates folktales must have an audience who verbally cheers, reacts to the climax of a scene, and helps the performer build up the spiritual and physical energy needed for the culmination of the story.

A combination of singing, called “chang,” plus verbal storytelling called “aniri,” and body language called “neoreumsae,” a pansori piece can go on for up to eight hours. The drummer sets the pace, while the audience energizes the storyteller with encouraging shouts, adlibs and cheers.

The word “pan” in pansori means gathered crowds and the “sori” means singing or storytelling in front of an audience.

Added to UNESCO’s List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2003, pansori has been popular with the masses, but the pansori repertoire is riddled with old proverbs and idioms.

“Gwangdae,” which originally referred to mask-wearing performers, became the trade name of pansori singers during the Joseon period, according to written records.

When Yangban started singing pansori, they institutionalized the repertoire with Hanja-based vocabulary and elevated pansori into an entertainment genre enjoyed by the kings.

“Many of the documented early pansori singers are ‘seondal,’ the educated Yangban who did not hold government posts. When gwangdae went around the country telling stories of corrupt bureaucrats and tragic stories of people’s sufferings, the central government acted on the news and would dispatch undercover inspectors to the regions appearing in pansori stories. The pansori-performing gwangdae were intelligence gatherers who had access to ears of high-ranking officials and even the king,” said Kim Yong-geun, director of Jirisan Cultural Resources Research Center, who has been researching pansori since 1987.

Entertainers perform in the Bubyeongnu yeonhoedo section of the “Welcoming Banquet for the Governor of Pyeongan” by Joseon painter Kim Hong-do (1745-1806) on display at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul.Photo © Hyungwon Kang

Namwon City in South Jeolla Province has a long tradition of big names in pansori establishing Dongpyeonje, the style of pansori developed in areas east of the Seomjin River, centering around Namwon and Gurye. Seopyeonje originates from areas west of Seomjin River, including Gwangju, Gochang and Jindo.

Song Heung-rok (1801-1863), one of the founders of Dongpyeonje pansori, even held a very high ranking government post, Jeong 3-pum, a third position in ranking from the top. He is revered in his hometown of Namwon, North Jeolla Province, along with 49 accomplished pansori singers from the Joseon period, also known as pansori myeongchang.

One of the classic pansori, “Simcheongga,” is a story set in the year 1085 during the Goryeo Kingdom, of a woman called Sim Cheong who becomes an empress.

Sim Cheong, in an effort to have her blind father Sim Hak-gyu regain his eyesight, jumps into the sea as a human sacrifice offered to placate the sea gods. Her filial piety moves the gods and she becomes an empress upon resurrection. At the palace, Sim Cheong invites blind people from all over the land.

The blind father travels a figurative thousand li, about 400 kilometers, to reach the Emperor’s Palace where, upon discovering his daughter, he regains his eyesight in a state of extreme shock.

The entertainment is enhanced when pansori is articulated in emotionally charged song, along with a tragic story line and emphatic expression of body language.

Such is the scene in which Lady Gwak, Sim Cheong’s mother, dies after giving birth -- the pansori singer collapses onto the floor, landing on her bottom and wails loudly with tears running down.

“Crying and wailing is the most difficult and draining part of pansori, as it takes a lot out of you,” said Myeongchang Heo Ae-sun, 54, of the National Folk Music Center. Heo has completed singing the entire four-hour “Simcheongga.”

A pansori drum, which was custom made according to Joseon Dynasty specifications by Kim Yong-geun, director of Jirisan Cultural Resources Research Center in Namwon, North Jeolla Province. Photo © Hyungwon Kang

Heo’s mother, Ahn Jeong-ja, 76, is a Jindo Ssitkkimgut shaman. ”When I first told my mother that I would like to learn pansori, my mother was elated and signed me up for pansori lessons,“ Heo said.

But although the singers are cheered on, pansori is an exhausting performance.

“It takes a lot of energy. Several people I know don’t want to perform the complete songs, saying it causes shortened lifespan,” said Heo.

“I built up my stamina and strength for at least two months before the performance. I’m a picky eater usually, but during that month I ate lots of meat combined with cardio exercises and stretching,” said Heo. “I gained at least 2 kg in the last month,” Heo added.

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

---

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed.

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)