Experts say diverse lifestyles reflect changes in socio-economic environmentLee, a 65-year-old woman who lives in an apartment near the Han River in Seoul, has recently been troubled with the small dog her daughter leaves with her on weekdays.

Her married daughter, 33, began keeping the dog a few months ago and felt sorry leaving it at home alone while she and her husband were at work. So she asked her mother to take care of the dog while she worked.

When Lee has to go out, her daughter reluctantly leaves the dog at a pet store in the neighborhood. Her daughter and son-in-law often walk their dog in the riverside park at night.

Lee does not mind that the couple loves their dog like a child. What worries her is their reluctance to have a real child. Before getting married, the couple told their respective parents that they would not have children in order to focus on their careers. Lee now just hopes her daughter and son-in-law change their minds.

A friend of Lee’s, who lives in the same neighborhood, has a different concern about her 36-year-old daughter who has no plans to marry and is happy to be single for the rest of her life. The daughter has lived separately from her parents in a rented one-room apartment in southern Seoul for years.

“It seems that my daughter feels no unease over her life as many of her friends have led a similar life,” said the mother who wished not to be named.

In a sharp contrast to these two daughters is the life of female writer Gong Ji-young, 48, who has married and divorced three times, and lives with her three children, each of whom has a different biological father. Based on her experience, she published a novel titled “My Pleasant House” in 2007, which received a warm response from many readers, married and unmarried.

Broadcaster Huh Soo-kyung sparked controversy in 2007 when she gave birth to a girl through artificial insemination without a husband after marrying and divorcing twice. Huh, then 41, told a TV talk show months before delivery that her mother had advised her to become a single mom as it would help her lead a better life.

The contrasting cases of the four women reflect just part of diversifying types of families in Korean society and its changing perception of family, which is defined sociologically as a group of people affiliated by consanguinity, affinity or co-residence.

Diversifying patternsIn the process of industrialization and urbanization since the early 1960s, the country’s typical family structure saw a dramatic transition from extended family to nuclear family. In traditional Korean society, which heavily relied on agricultural production, more than three generations living under the same roof was the usual and ideal family pattern. But rapid urbanization accompanying industrial growth made the nuclear family comprising a husband, wife and their children the new dominant type.

In the 1990s, the emergence of the “Dink” family ― a couple where both spouses earn incomes but shun having kids ― sparked controversy here. Some elderly people criticized the young generation for avoiding the responsibility of bringing up children. The “Double Income, No Kids” couples argued that they just wanted to live a free and affluent life different from their predecessors’.

The Dink family is now such a familiar phenomenon that people accept the concept of the “Dink Pet” family like that of Lee’s daughter and son-in-law with little curiosity.

In recent years, Korean society has seen even more variation in the composition of families, which experts note reflects a wide range of changes in socio-economic conditions and values.

With remarriages becoming more common, the “patchwork” family, in which mixed parents ― one or both parents remarried ― bring children of the former family into the new family, is no longer seen as unusual. According to figures from Statistics Korea, the ratio of marriages where both spouses remarry accounted for 12.8 percent of total marriages in 2009, up from 4.7 percent in 1990.

Though still small in number, a new trend is the “community” family, in which a group of people in similar circumstances or sharing similar views on life live together. “I know of 16 unmarried women in their 40s and 50s living under the same roof,” said Kim Seung-kwon, a research fellow at the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

The single-parent family is also becoming more accepted. The majority of single-parent families are single-mother families rather than single-father ones with a growing number of women having the resources to rear their children by themselves.

Another growing trend is grandparents who have taken responsibility for raising their grandchildren.

A teacher at an elementary school in Seoul said about 10 percent of students in each class live with grandparents or a single parent. “I no longer tell my students to write ‘I love Mom and Dad’ on the ribbon carnation they make on Parents’ Day,” said the 38-year-old teacher who wanted to give just his family name Kim.

The number of single-person households, including unmarried or divorced and elderly people living alone, has also been increasing. Experts attribute the increase in single-person households to prolonged life expectancy, increase in divorces, deferred marriages and decline in weddings. Figures from Statistics Korea show the number of marriages decreased by nearly 25 percent over a decade to about 309,700 in 2009. Nearly 30 percent of Koreans in their 30s were unmarried as of last year, up from 6.8 percent in 1990 and 13.4 percent in 2000.

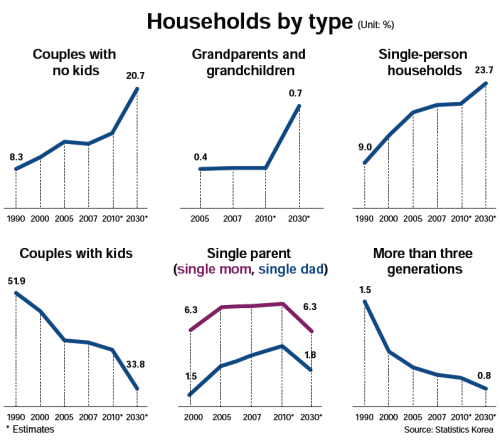

According to data from Statistics Korea, single-person households accounted for 20.1 percent of the total households in 2007, compared to 9 percent in 1990. The figure is projected to rise to 23.7 percent by 2030.

The numbers of single-parent families and couples without a child were also up from 7.8 percent and 8.3 percent in 1990 to 8.6 percent and 14.6 percent in 2007, respectively. Experts estimate the figures will reach 8.1 percent and 20.7 percent by 2030.

Meanwhile, the ratio of families comprising parents and children decreased from 51.9 percent in 1990 to 42 percent in 2007 and is forecast to be further down to 33.8 percent in two decades.

Kim, the researcher at the KIHSA, said the shift in values from blood bondage to individualism, coupled with increasingly tight economic conditions, has helped accelerate the recent transformation of family structure. “Furthermore, government and corporate policies have not been family-friendly enough,” he said.

Some express concern about the dissolution of what they regard as normal families, which have the key functions of producing and socializing children as well as serving as a basic cell for society’s structure.

They also emphasize the need to preserve the value of the family as a “haven from the world,” which encourages intimacy, love and trust to help individuals escape from the competition of modern society.

Changing attitude

But others argue that whether or not one views the concept of family as declining depends on how family is defined. They say it is no longer relevant to stick to the sociological distinction between a traditional family consisting of a bread-winning father and a stay-at-home mother raising their biological children and nontraditional one deviating from this rule.

Koreans have become increasingly accepting of the diversifying types of family and the various ways of life their contemporaries have chosen.

“People live different lives. I thought no one should try to apply his or her own ruler to another person’s way of life,” said a 41-year-old woman surnamed Kim, who runs a publishing company.

The broadcaster Huh’s revelation of her plan to give birth to a test-tube baby drew criticism at the time from some saying that she was selfish not to consider how her child would feel growing up without a father. But quite a few people expressed sympathy with her choice, saying no one is entitled to judge Huh from his or her own perspective.

Now, one in every 10 Koreans getting married is tying the knot with a foreigner. Government figures show the number of Koreans taking foreign spouses increased from 4,710 (1.2 percent of the total marriages) in 1990 to 42,356 (13.5 percent) in 2005 before sliding to 33,300 (10.8 percent) in 2009.

Koreans are now also accustomed to same-sex couples, with few expressing curiosity over English musician Elton John and his partner David Furnish attending the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton in London in April.

Experts note that in modern society people are inclined to choose mates based on love and affinity beyond blood bondage and marriage, prompting a societal shift toward favoring emotional fulfillment over relationships within a family.

“If we share love, then we are all a family,” said Gong, the female writer, in an interview with a local daily.

According to researcher Kim, the increasing individualization of Koreans, while accelerating the dissolution of the traditional family, is also helping create new family patterns bonded by shared emotion and interests rather than consanguinity and marriage. “A growing number of people form cyber families, which allow them to share their concerns online with someone they have never met,” said Kim.

Experts call attention to the need to strengthen support for some types of families that are financially and socially vulnerable, such as grandparents taking responsibility for raising grandchildren, elderly people living alone and immigrant wives and their children.

The number of grandparents-grandchildren families increased from 35,194 in 1995 to 45,225 in 2000, 58,101 in 2005 and 69,175 in 2010, according to figures from Statistics Korea. The reasons ranged from parents’ divorce and remarriage (53.2 percent) to their running away from home (14.7 percent), disease or death (11.4 percent) and unemployment or bankruptcy (7.6 percent).

Vulnerable families

A survey of 51,852 families of these types last year showed their average monthly income stood at less than 600,000 won ($550), far below the minimum cost of living.

The average age of grandparents raising grandchildren was 72.6, with half of them relying on support from the government and public welfare institutions.

In more than 82 percent of cases, one grandparent raised his or her grandchildren alone. In addition to financial challenges, these grandparents have difficulties helping with grandchildren’s school life and preparing them for the future. Eight in every 10 grandparents suffer from diseases.

A recent survey by the Seoul Metropolitan Government found more than 20 percent of the 1 million people in the city aged 65 or above live alone, many of them financially struggling. More than six in every 10 elderly people living alone are homeless.

With an increasing number of women from other Asian countries marrying Korean men mostly in rural areas, experts call for strengthened efforts to protect them from domestic violence and help them adapt to Korean society.

They also raise the need to secure education opportunities for children from multicultural families to ensure their smooth assimilation into the society. Recent government figures showed that about 80 percent of children from multicultural families aged 7 to 12 attend elementary school but the ratio falls to 60.6 percent for middle school and further to 26.5 percent for high school.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)