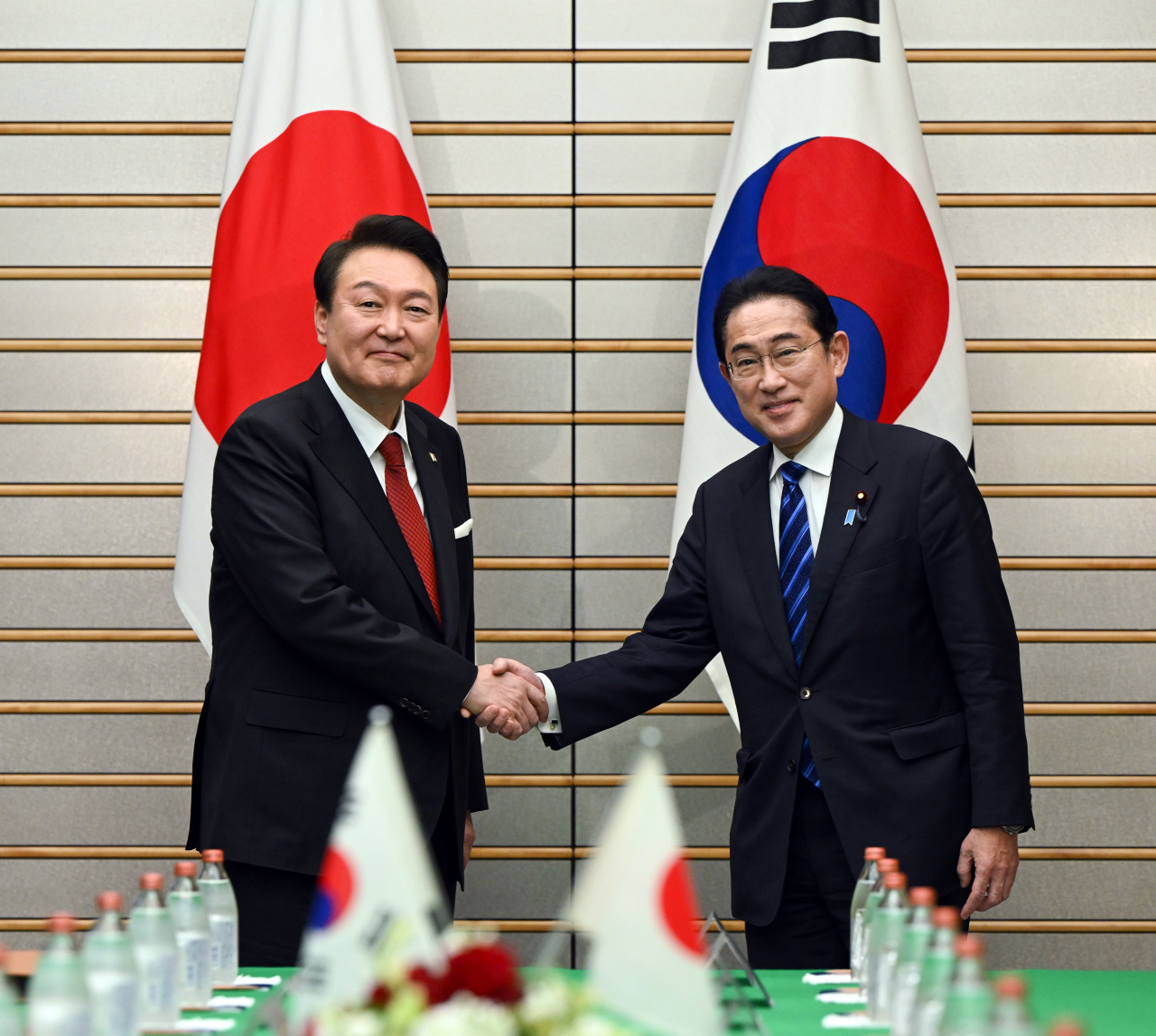

Despite the latest deal with Japan meant to end a historical dispute over forced labor, the Yoon Seok Yeol administration is facing a public backlash as the division deepens over whether Yoon has ushered in the right kind of closure. Some experts say the president may just have done so, as South Korea in the long-term can claim the “moral high ground” on the issue.

In a potential move against a 2018 Korean court ruling holding Japanese companies liable for damages to Korean victims of forced labor during Japan’s 1910-45 rule of the Korean Peninsula, Seoul plans to compensate the victims on its own, while waiting for Tokyo to pay into a separate joint fund set up to improve relations.

Yoon reaffirmed the decision at a two-day summit that ended Friday in Tokyo with his Japanese counterpart. Ahead of the meeting -- held for the first time in 12 years to start repairing ties -- Yoon’s foreign minister revealed the plan on March 6, prompting a public outcry. Opposition lawmakers called Yoon out for an “unwarranted capitulation,” because he skipped “an official apology and direct compensation.”

“Aside from politicians doing little to prevent anti-Japan sentiment from getting out of control when doing so works to their advantage, I think everything involving Korea-Japan relations comes down to this: a one-on-one match where there is an immediate win or defeat,” said Lee Won-deog, a professor of Japanese studies at Kookmin University.

Therefore, Lee noted, anything that falls short of the expectations Korea has for Japan to make up for its colonial wrongdoing is considered a “concession” -- a course of action often reduced to surrendering to an “old foe,” no matter how small such an exchange takes place for gains later.

“Whether that kind of narrow thinking serves us best is something we need to revisit, strategically,” Lee said, adding, “Korea is essentially seizing the moral high ground,” as it leaves the door open for the Japanese to apologize for the Korean victims and pay them the damages. The Japanese firms have repeatedly refused these two steps, citing the 1965 treaty that normalized bilateral ties following Seoul’s independence from Tokyo in August 1945.

Park Cheol-hee, a professor of Japanese studies at Seoul National University's Graduate school of International Studies, echoed this sentiment, saying it is now up to Japan to “make a move commensurate with” what Korea has publicly offered to do.

“Well there is a scenario in which Japan keeps doing nothing -- no apology or compensation whatsoever. But where does that leave Japan? I mean on the international stage,” Park said of international practices to keep holding countries accountable for their wartime wrongs, in particular human rights violations that often invite bipartisan support.

More specifically speaking, Park added, the US could demand a more “proactive role from Japan to heal ties,” still seemingly miles away from complete closure. He was referring to the three-way US-led military coalition that has been working on North Korea’s denuclearization. Washington has openly pushed for stronger Seoul-Tokyo ties. America’s two biggest Asian allies are also part of the US-led chip, called Chip 4.

Such US outreach could be a stretch, Park acknowledges. “But in that case, we can definitely say to anyone asking who’s to blame for the lukewarm ties: ‘We have done everything, pulled every stop and exhausted all avenues for the ties to work. It’s Japan not returning the favor,’” Park said.

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)