China’s strict “zero-COVID” policy ended last month, but the movement of defiance against Chinese President Xi Jinping continues.

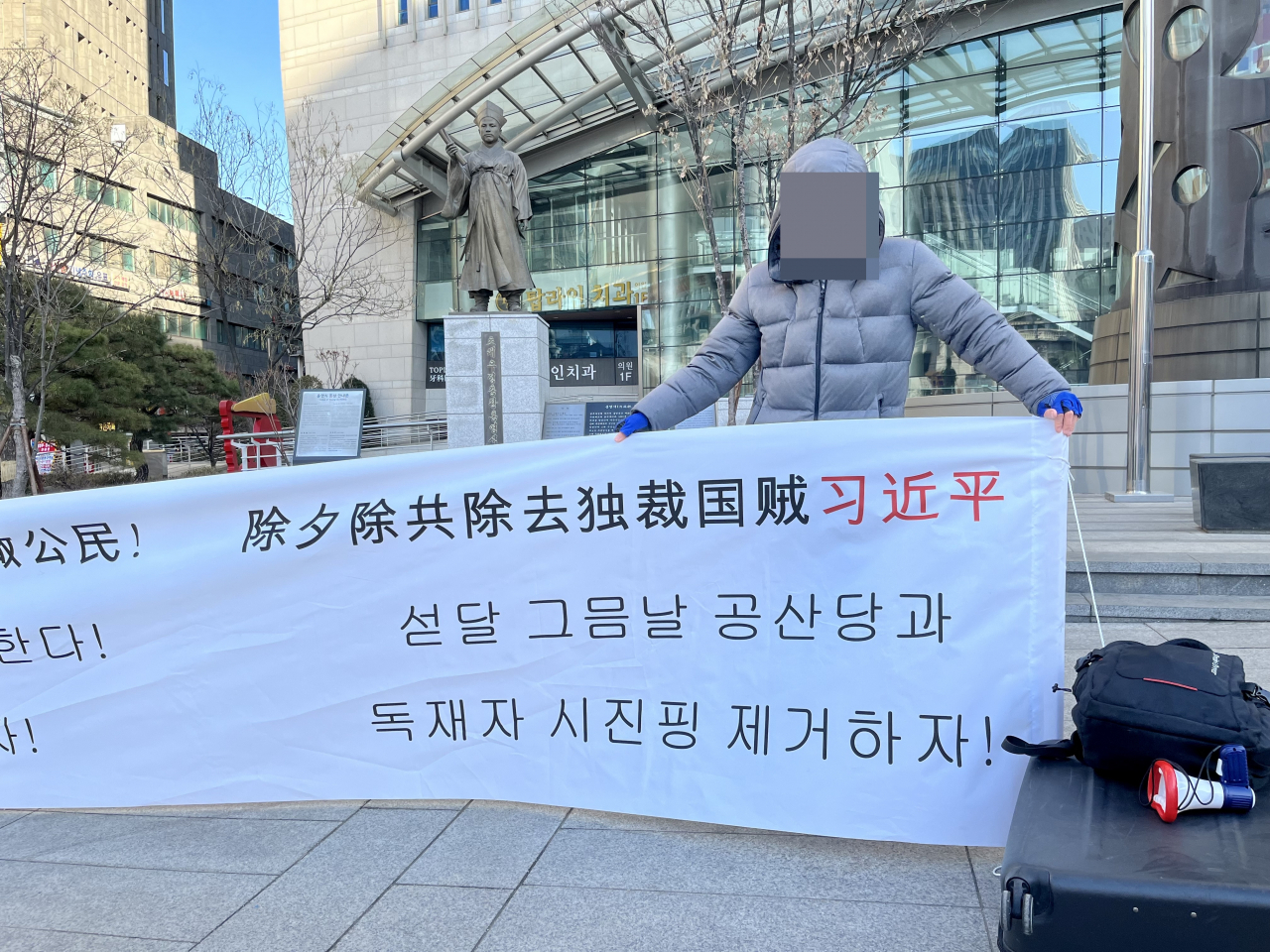

On Lunar New Year’s Eve on Saturday, a small group of Chinese people gathered near the Embassy of China in Seoul for the fourth “white-paper” protest to take place here. The movement against COVID-19 restrictions came to be known as white-paper protests after people in China held up blank sheets of papers to express discontent and dodge censorship.

Outside the post office less than 200 meters from the Chinese Embassy in Seoul, demonstrators stood with a large banner reading: “We want free speech, not censorship. We want respect, not lies. We want election, not dictatorship. We want to be citizens, not slaves.”

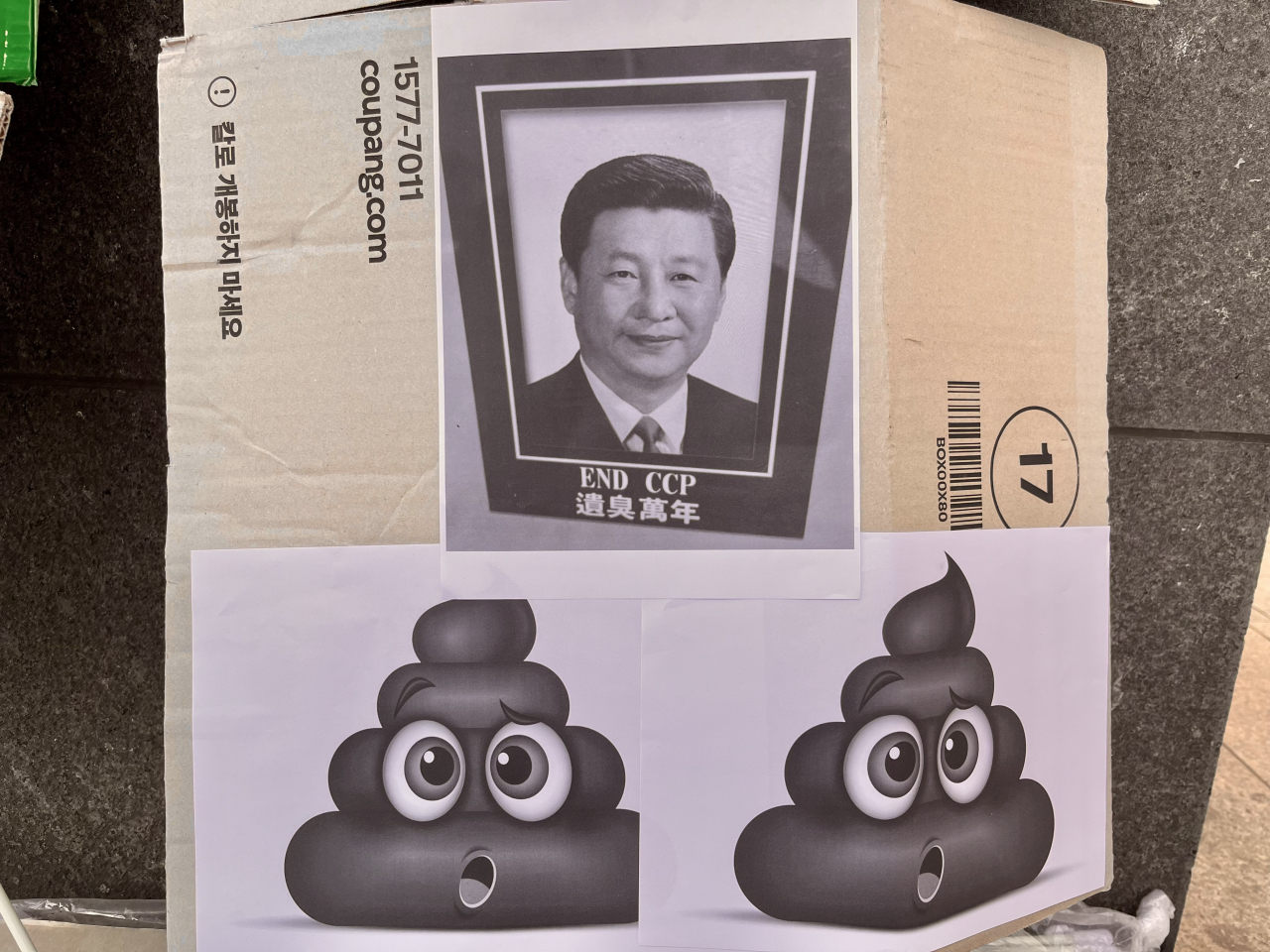

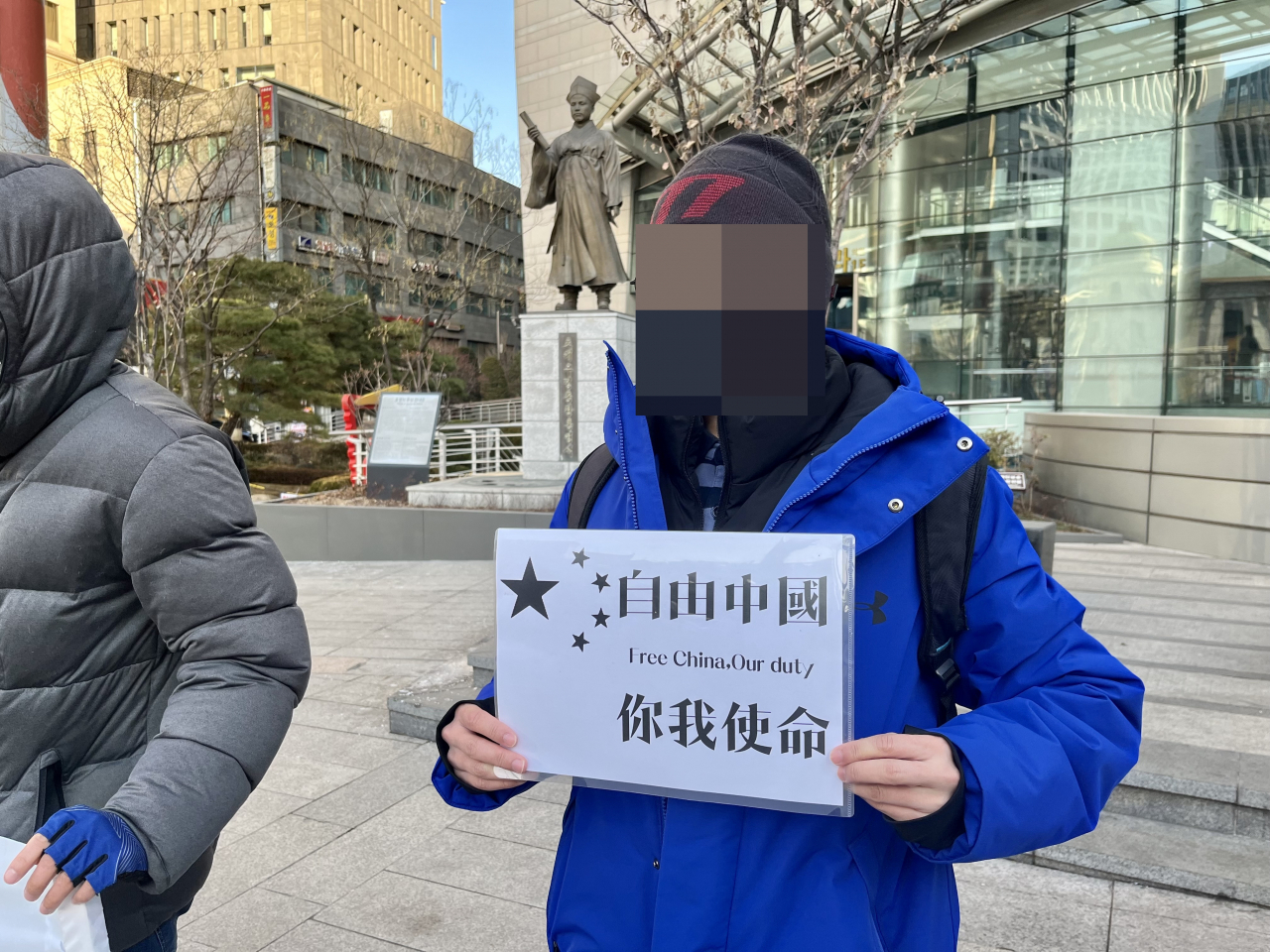

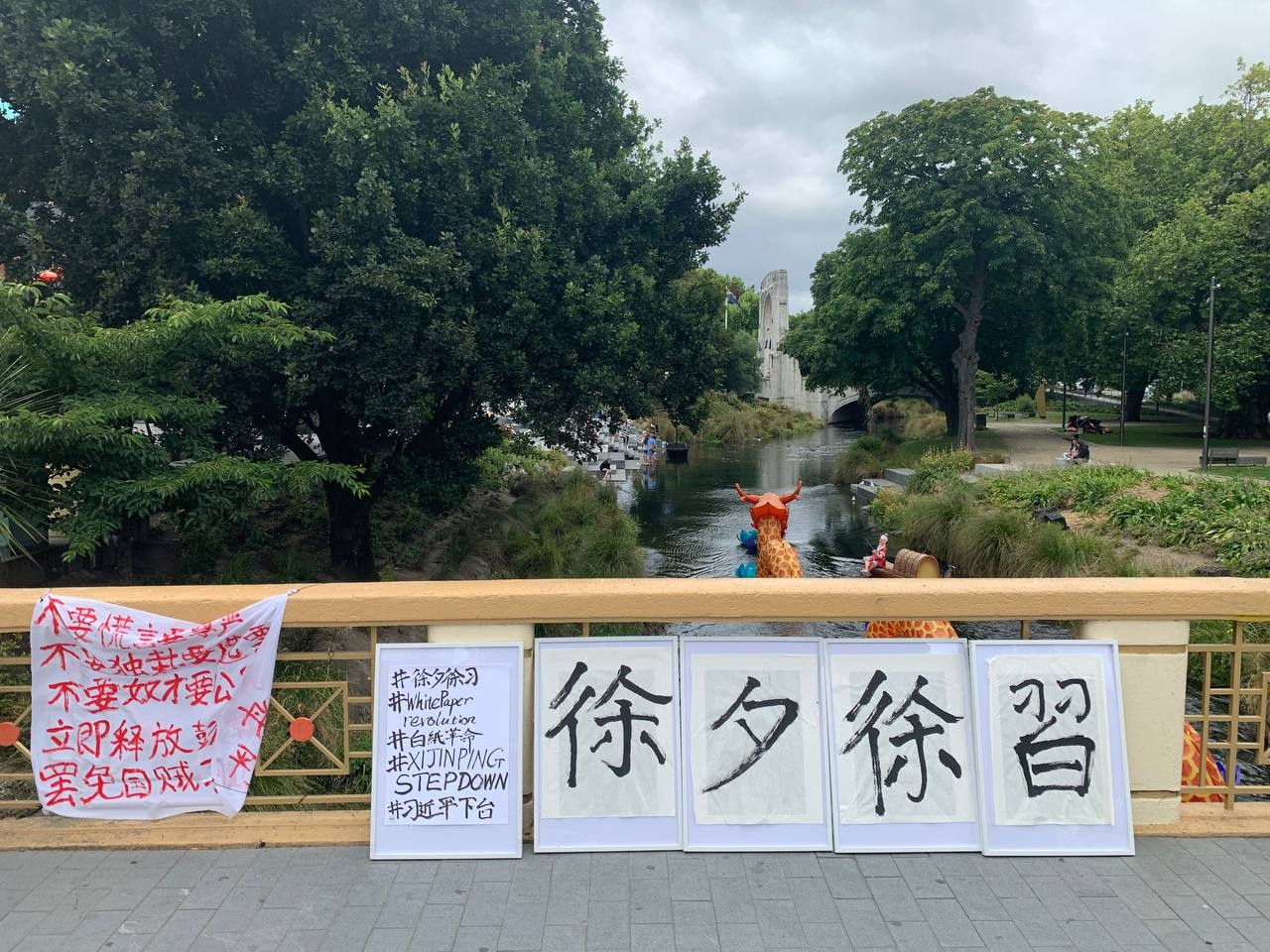

Other signs and placards at the protest site read: “Down with the Chinese Communist Party, down with dictator Xi Jinping,” “Give me freedom or give me death” and simply “Free China.”

A 20-something student at the site told The Korea Herald the protests were “never really just about lockdown.”

“At its core, it’s an anti-CCP protest. Xi is a dictator and we want him gone.”

He said among young Chinese like himself, “the anti-CCP sentiment is very strong.”

“Zero-COVID is over, yes, but there has to be a more fundamental, lasting change to China. A lot of younger people in China around my age don’t agree with how Xi and the CCP are running the country.”

Another participant, who said he was in his 30s, said the end of zero-COVID did not mean people in China now had freedom.

“Chinese people have always lived under oppression like slaves long before the pandemic hit. I lived in China all my life until my family moved here five years ago, so I know,” said the man, who said he was from near Beijing.

He agreed that among younger people in China, there was “pent-up frustration” with the CCP.

“We’re not like our parents’ generation. I honestly believe a nationwide movement for democratization could break out in China in three to five years because so many people have had enough,” he said.

“When that happens I’m going to go back to join the movement, and help my people.”

He said he was able to speak up “from the comfort of no longer being in China.”

“I can say everything I’m saying right now because my parents and I live in Korea. If I said something like this China, the police would come after me, and you will never see me again,” he said.

For him, he said the ultimate reasons for participating in the protests were to “turn China into a free, democratic country, like the US or Korea.”

“I think there are a lot of people in China who feel the same way. They’re only silenced by fear.”

On the dwindling turnout, the participant in his 20s said he believes fear is a “big factor.”

Protesters take pains to prevent their identities from becoming known to the Chinese police, he said. They wear hats, sunglasses and face coverings and try to keep their communication as discreet as possible.

“Your phone is being spied on so I tell people not to bring their phones when they’re coming to the protest,” he said. “I tell them not to even dine nearby the protest. Sometimes we don’t give out our real names to people we meet at the protest because you never know.”

He said that many of the people, mostly students, he had met in previous protests in Seoul were unreachable now. “I’ve tried to contact them but they’re not responding. I don’t know where they are now,” he said. “I can’t find them.”

People returning to China for the holiday had to erase any trace of their participation in the protests from their smartphones, and left the anonymous group chats they used to communicate with others either participating in or supporting the protests, he said.

“If you tell your friends about it or send photos on apps like WeChat then the Chinese police can find out. I didn’t tell people I was going to these things because you can get tracked,” he said. “It’s scary, especially if you have family in the mainland.”

There was also the challenge in coordination and planning, as the protests weren’t “being led by an organizer or a certain group,” he said. “That’s how it’s been since the beginning. Words spread and we just kind of got together.”

In China, some people who attended white-paper protests last year "vanished" -- allegedly detained, according to reports. Peng Lifa, who posted anti-Xi banners over a highway in central Beijing in October, has been missing from public view since authorities caught him in the act.

“We don’t know what happened to Peng Lifa other than that he was taken into custody. There are dozens of others who similarly ‘disappeared,’” he said.

He said overseas Chinese are “definitely safer.”

“I can’t speak for everyone but being in Seoul I feel safe. The Korean police respect our right to protest. So far I haven’t felt like I need to shush,” he said.

“But it’s been only one month or two since we began opposing the CCP this way, so we’ll have to see.”

Now may be the “last chance” for his country to change and democratize, he said.

“Chinese authorities are sophisticating and stepping up their surveillance systems with AI technology. If we wait, I don’t think we will have much chance against the new surveillance technologies,” he said.

“So we feel that we definitely have to act now, or it’s going to be too late.”

A third participant said he hoped there would be more support from Korea and the international community “because they are not at risk, unlike us.”

He said he regrets that Chinese were not there for Hong Kongers during their wave of protests in 2019.

“I really regret that we didn’t help with the Hong Kong protests back then. We should have stood with them but I think many of us just didn’t know better,” he said. “But I hope we can still learn from them. We are fighting against the same thing.”

A Korean university student in his 20s, who was at the protest briefly, said he was “rooting for the people of China.”

“I saw it in the news that this is the largest pro-democratization protest in China since the Tiananmen massacre,” he said.

“I feel like Chinese people are standing at an important crossroads in their history. If they fail to win this time, the Communist Party will make their one-party dictator rule even more impregnable than it already is. So I support their fight.”

Saturday’s protest in Seoul was one of several white-paper protests held the same day in cities around the world, including in Los Angeles, The Hague in Netherlands, Stuttgart in Germany and Christchurch, New Zealand.

In Chinese cities including Beijing over the weekend, people set off fireworks, defying the ban on fireworks and firecrackers.

Dilemma for Xi?

The pandemic likely served as a trigger for the Chinese public to express their already existing woes with intensifying repression, according to Moon Heung-ho, head of the Institute of Chinese Studies at Hanyang University in Seoul.

“Before this point, public discontent rarely translated into tangible expressions like protests due to the state’s harsh crackdown,” he said in a phone call with The Korea Herald.

He said the latter days of the pandemic were an “awakening for Chinese people” who had to live through punishing lockdowns for three years.

“In 2020, China prided itself on its successful response. The US and countries in Europe were struggling with large outbreaks while China seemed like it was faring better with its tight controls. Then, it looked like China’s approach was working, even superior,” he said.

But as the years went on, life began to return to normal in other countries as China continued to remain under extreme lockdown.

The white-paper protests “helped expedite the end of the zero-COVID,” Moon said. “It became harder for Chinese authorities to justify adhering to their tough policy.”

“COVID was like a magnifying glass that exposed China’s intense repression, not only to its people but to the rest of the world as well.”

Kang Jun-young, a professor of Chinese studies at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, said it would “come as a shock” for Xi that the young generation who grew up after patriotic education was instituted in early 1990s is pushing back.

“Young people in China grew up believing their country was a global superpower to rival the US,” he said. “They’re not very happy now. About 1 in 5 college graduates aren’t landing jobs.”

He added, however, that it would take “a lot more” for the anti-CCP protests to amount to an actual threat that can subvert Xi or the party.

“The protests may have ended zero-COVID, but they didn’t change the CCP,” he said. “China is able to quash mass unrest with police crackdown and surveillance, if Hong Kong is any example.”

He said because there is no other political power there to rival the CCP, protesters do not have an alternative or a group they can organize around. “Without such center, it is easy for protests to lose momentum,” he said.

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)