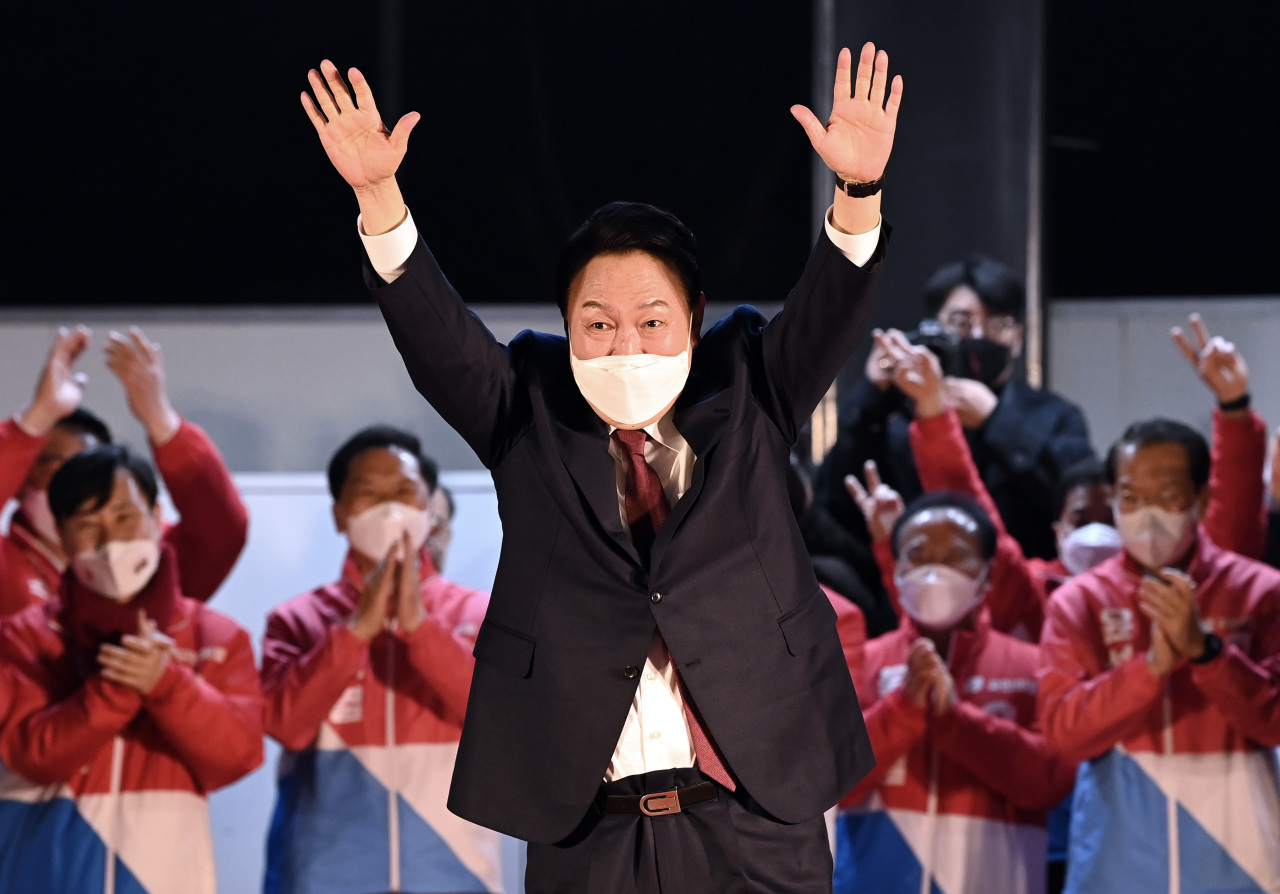

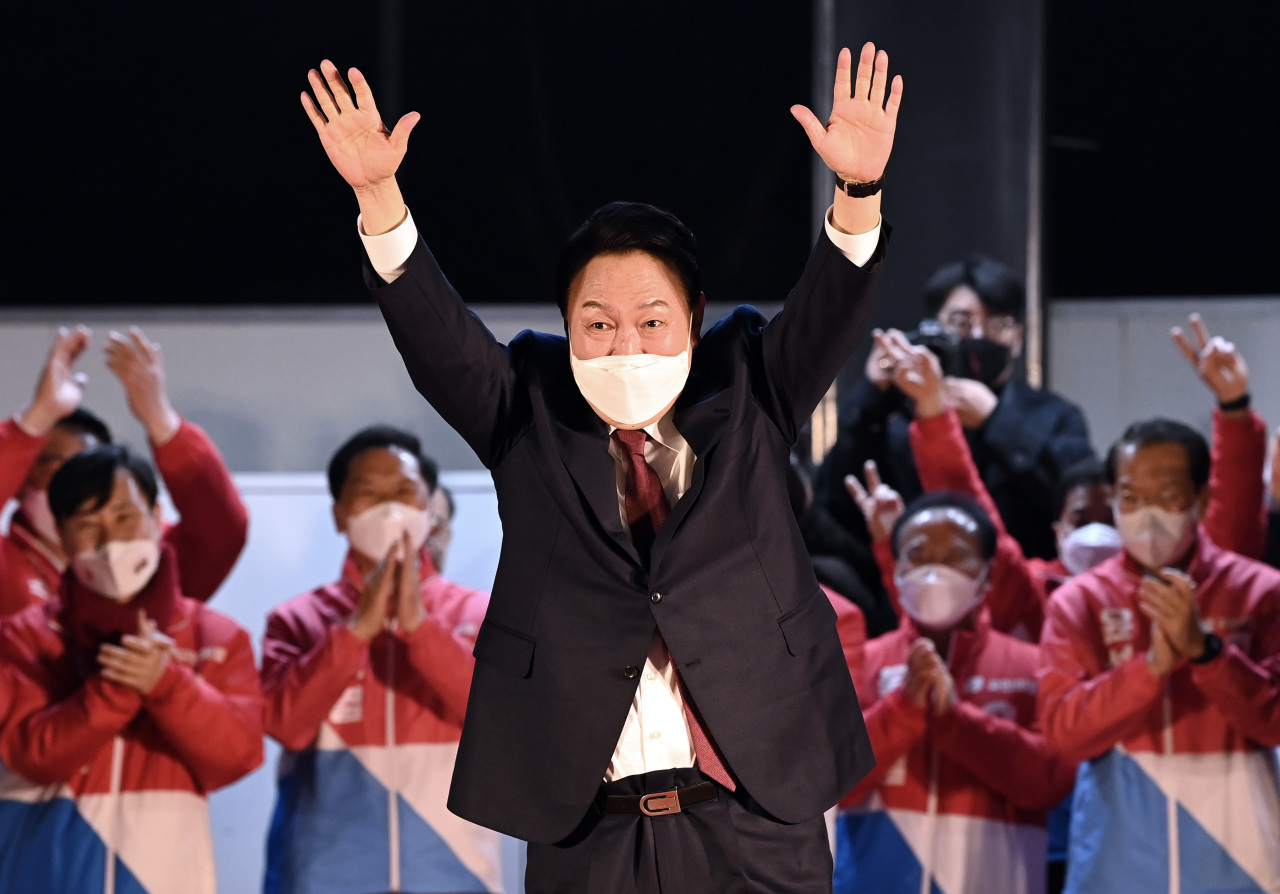

Yoon Suk-yeol of the main opposition People Power Party greets supporters in front of the party`s headquarters in Seoul on early Thursday morning after he was declared as the winner of the 20th presidential election. (Joint Press Corps)

The dramatic victory for Yoon Suk-yeol of the People Power Party marks a shift for South Korea where voters veered back to give support to the right after five years of the liberal faction rule under President Moon Jae-in of the Democratic Party of Korea.

Yoon's win symbolizes South Korea's wish to bring justice and equality to society after many felt the opposite in the performance of the Moon administration, which also came to power from voters’ yearning for the same five years ago.

Many voters were angered to find Moon making controversial picks for key posts and allegedly aiding his allies while pushing a controversial agenda. The Democratic Party unilaterally pushed through its own initiatives, bluntly neglecting naysayers in the process.

Candlelight protesters entrusted Moon to enact equality and justice, but no major political reform has apparently taken place, and even the reform measures that were brought forth have not yielded anticipated outcomes.

Voters showed their will to overthrow the Moon administration and bring yet another change by awarding an overwhelming win for the People Power Party in the April 2021 by-elections, and despite being in a smaller margin, they have done it once again in the presidential election.

Yoon emphasized from very early on in his campaign that he is a candidate who can bring back justice to Korean society, as evidenced by his long prosecutorial career highlighted by rigorous investigations into both main political factions.

The former prosecutor general was a major figure behind the investigation into corruption and embezzlement by impeached President Park Geun-hye of the conservative bloc, and he also ordered investigations into power abuse charges of former Justice Minister Cho Kuk, a close confidant of Moon.

South Koreans have fervently demanded justice and impartial government rule from early on, since controversies on Park arose and drove people to stage protests for months until her eventual impeachment and removal from power. They demanded a figure to represent the core values of a democratic government and work for the people while keeping those in power accountable.

Yoon's perceived history of staying loyal to the people, not to particular factions, was enough for voters to bet on a political novice to lead the government, if justice and impartiality can be assured in the process.

The president-elect now faces leading a minority government after being elected, and is expected to face much opposition from the National Assembly dominated by members of the Democratic Party.

Yoon had vowed to collaborate with figures across different parties, and his vision could be reflected in the process of forming the Cabinet.

The fact Yoon won the race only by a small margin against his rival means the public sentiment is not entirely supportive of him and his party, and deals will have to be made with other parties and factions for his administration to really move forward and bring changes.

That means his victory creates leeway for South Korea to again attempt forming a coalition government and fulfill voters' wish to see bipartisan, clean politics realized.

Experts believe Yoon will attempt to recruit some major figures from the Democratic Party to join his government in key ministerial posts, while following up on the terms he reached when uniting candidacies with Ahn Cheol-soo of the minor centrist People’s Party.

"There really isn't much that Yoon Suk-yeol can do as the president in this deadlocked situation with the Democratic Party-dominated National Assembly," local political commentator Rhee Jong-hoon told The Korea Herald.

"He will be forced to make bipartisan picks for his Cabinet in running his government, even though we can't be sure if the Democratic Party will be willing to join at his suggestion."

The Democratic Party alone controls 172 out of 300 legislative seats at the National Assembly, meaning Yoon and his party could face challenges in carrying out any of his promised policies and initiatives.

The prosecution is believed to gain more power and authority upon Yoon’s victory, partly from his prosecutorial background and also from the expected opening of fresh investigations into alleged corruption by Yoon’s presidential election rival Lee Jae-myung of the Democratic Party and the Moon administration.

Yoon openly expressed his intent to launch a probe into the incumbent administration if elected, which has been viewed by opponents as the intent to engage in "political revenge."

If the probes commence as vowed, the investigations will likely be a continuation of the troubling history for past South Korean presidents. The Democratic Party is expected to widely use its parliamentary dominance to block such attempts.

Lee only fell short of victory by 0.73 percentage points, and 47.83 percent of voters lent their trust to the liberal party candidate. These two figures cannot be taken lightly, as any moves that disfavor these voters could be starting points for another troubling legacies South Korea could bear.

Democratic Party officials are also expected to pressure Yoon on allegations raised against him during the presidential race, which is something he will have to carefully respond to ensure voters continue to trust him to lead the administrative branch for the next five years.

Yoon has also faced suspicions of being involved in scandals of corruption in his prosecutorial years, as has his wife Kim Keon-hee on possible involvement in stock price manipulation and falsely reporting her credentials on her resume when applying for teaching jobs in the past.

While Yoon's victory means more voters were inclined to opt for the conservative bloc over its liberal rival, the outcome does not assure that South Koreans have turned conservative. It only emphasizes that the proportion of swing voters has grown and that the game of elections has become more than calculating votes by age group and regional party allegiance.

Voters have clearly gained more interest in involving themselves in the game of politics, as evidenced by the voter turnout of 77.1 percent, but they have also grown to make their political decisions based on their own interests and agenda, not from their traditional allegiance to political ideologies or interest groups.

What Yoon does in the early days of his presidency will also be crucial in determining the outcome of local elections scheduled to take place in June.

Although many experts had forecast months ago that the party that prevails in the presidential election is likely to extend a winning streak into the local elections, voters have shown they are almost evenly divided.

At this point, no political faction seems to have a clear advantage over others ahead of another key election. Voters could turn volatile depending on future course of events, and the political circle knows these electors are prepared to make considerate decisions in pursuit of self-interests.