Nurses in PAPR gear look after patients on ECMOs and other life support machines at the Medical Intensive Care Unit on Friday. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

INCHEON -- The second Christmas of COVID-19 has passed as South Korea battles its worst surge in the pandemic yet.

Just ahead of Christmas last year, the third big wave of COVID-19 had mainly swept across nursing homes. This Christmas, said Dr. Eom Joong-sik, an infectious disease doctor at Gachon University Medical Center, was “even more brutal” than the last. About half of the patients in the COVID-19 intensive care unit rooms of the hospital in Incheon had traveled from far-off cities, in search of a bed.

When The Korea Herald met Eom at the hospital on Friday afternoon, he said he started Christmas Eve as he does “any other day.” For over a year now, his hospital has played a key role managing Korea’s pandemic as a government-designated COVID-19 hospital.

“Since around mid-November all of our beds at wards for moderate to severe disease have been filled. Critical patients in particular have more than tripled,” he said.

He said that two of the hospitals’ eight ICUs -- including specialty units for heart, trauma, surgical or emergency patients as well as neonatal and pediatric units -- are now dedicated to treating COVID-19 patients only.

The glass screens operate on an interlock control system that is used to seal off areas with infection risks. The isolation unit is accessible via separate entrance and elevators to shield the rest of the hospital from a possible exposure. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

In the room adjacent to the ICU, infectious disease doctor Dr. Eom Joong-sik watches patients through remote monitors. This ICU treats “less severely ill” patients who don’t need to be mechanically ventilated, but still require high-flow oxygen therapy. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

On the 11th floor of the hospital is an ICU for “less critically ill” patients who, although on high-flow oxygen therapy, do not need to be mechanically ventilated.

Just hours after one of the 10 single negative-pressured rooms became vacant that afternoon, its next occupant had already been decided: a patient in the hospital’s semi-ICU who fell more severely ill. “Beds rarely remain empty for more than a day,” Eom said.

In an adjacent room overlooking the unit, nurses were checking on patients remotely. The room is equipped with large screens showing patients through a camera in each room and other monitors indicating vital signs like their heart rates, arterial pressures and oxygen saturation levels.

Patients whose vital signs fell outside an acceptable range were marked with a yellow alarm sign. Some of the patients were experiencing a drop in their blood oxygen levels -- which would normally measure 95 percent or higher -- to the mid-80s or lower, despite being on breathing support. That could indicate their chances of recovery were slim, Eom said.

The nurses in the virtual monitoring room communicated with protective-suited staff in the unit caring for the patients over the phone. One nurse could be heard telling her colleague, “Please check if TPN is being administered properly for the patient in room five.”

TPN, or total parenteral nutrition, delivers essential nutrients through a tube for patients who can’t eat on their own. Most patients in the unit were on some form of sedation so that their breathing patterns would not interfere with oxygen therapy, and given TPN.

The Medical Intensive Care Unit is where the most critically sick COVID-19 patients are treated. All of its beds have been fully occupied since mid-November. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

A nurse watches the patients remotely through vitals signs monitors and other patient-monitoring devices. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

This ICU is reserved for the sickest patients with COVID-19. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

In another ICU five floors down, the sickest COVID-19 patients on ventilators or other invasive life support machines -- such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or ECMO -- were being treated. All of the patients in this unit were “heavily intubated,” and unable to respond.

A few days prior, eight of these patients were ordered to cease care at the hospital based on a new government policy limiting the length of ICU hospitalization for COVID-19 patients to 20 days after the onset of symptoms. “Their 20 days were up. But see for yourself if any of them could be moved anywhere. One catheter gets pulled out accidentally, and the patient is dead,” Eom said.

One of the eight patients facing the executive order died a day after being told to leave, he said. As for the seven others, the ICU doctors were writing a letter to public health officials on why they had to stay.

Separated by glass doors, a nurse was watching the patients from remote monitors and performing other tasks to assist the staffers working inside the room. There were nearly as many nurses in big, white suits working the shift as there were beds.

As the patients required round-the-clock care, nurses had to be present nonstop. Naturally, to be able to alternate shifts lasting eight hours, there needed to be that many more staffers. “For every critical care patient, we would need at least three nurses, considering the shifts,” Eom said.

At the end of a shift, the staffers get out of personal protection equipment in a room with airflow ventilation and other infection control systems, to be discarded as medical waste. Then they head straight to the showers.

A poster on the wall in the changing room demonstrates proper steps to put on personal protective equipment. “Although it’s a routine procedure, it’s still important to remind ourselves,” Dr. Eom said. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

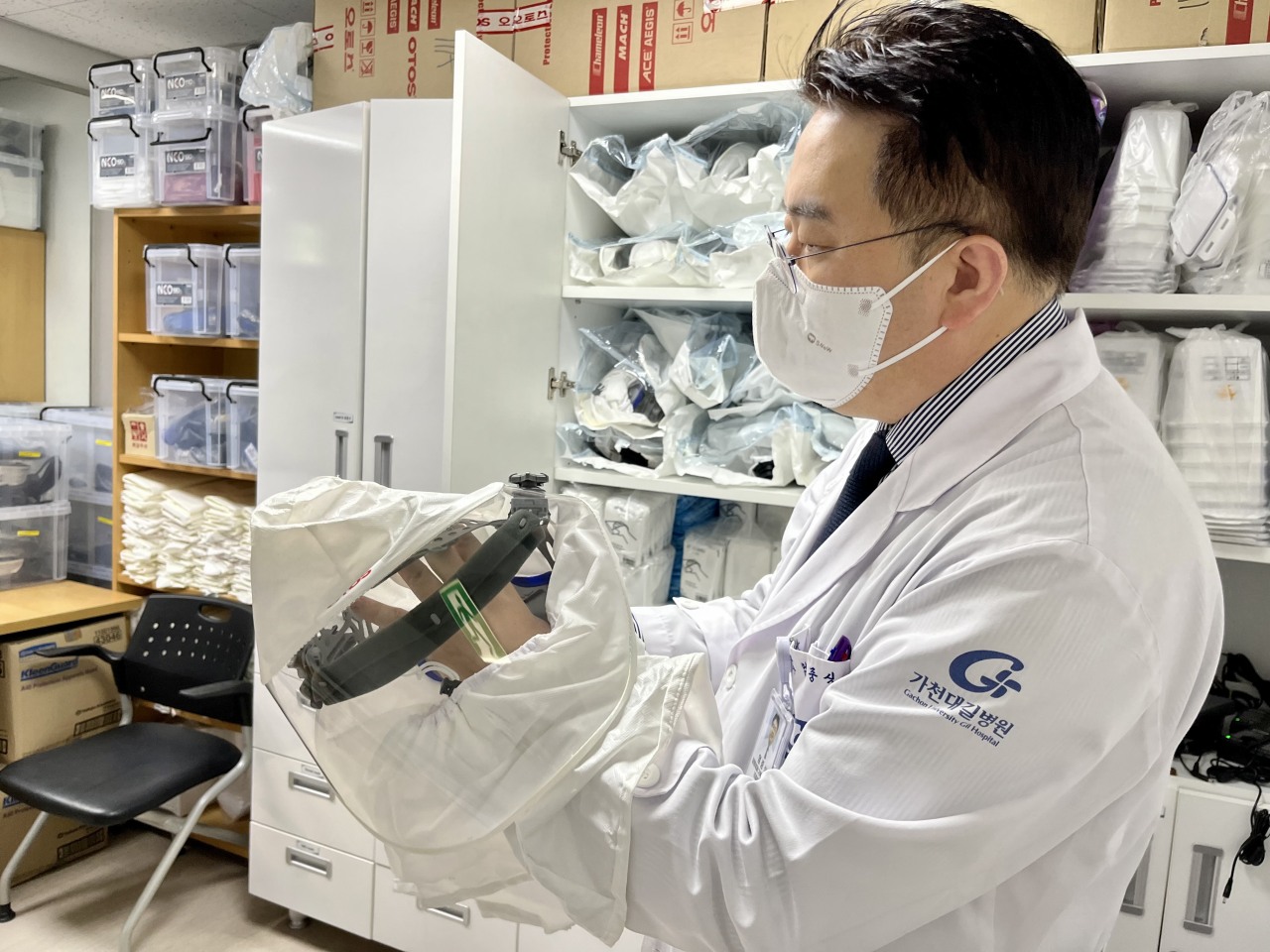

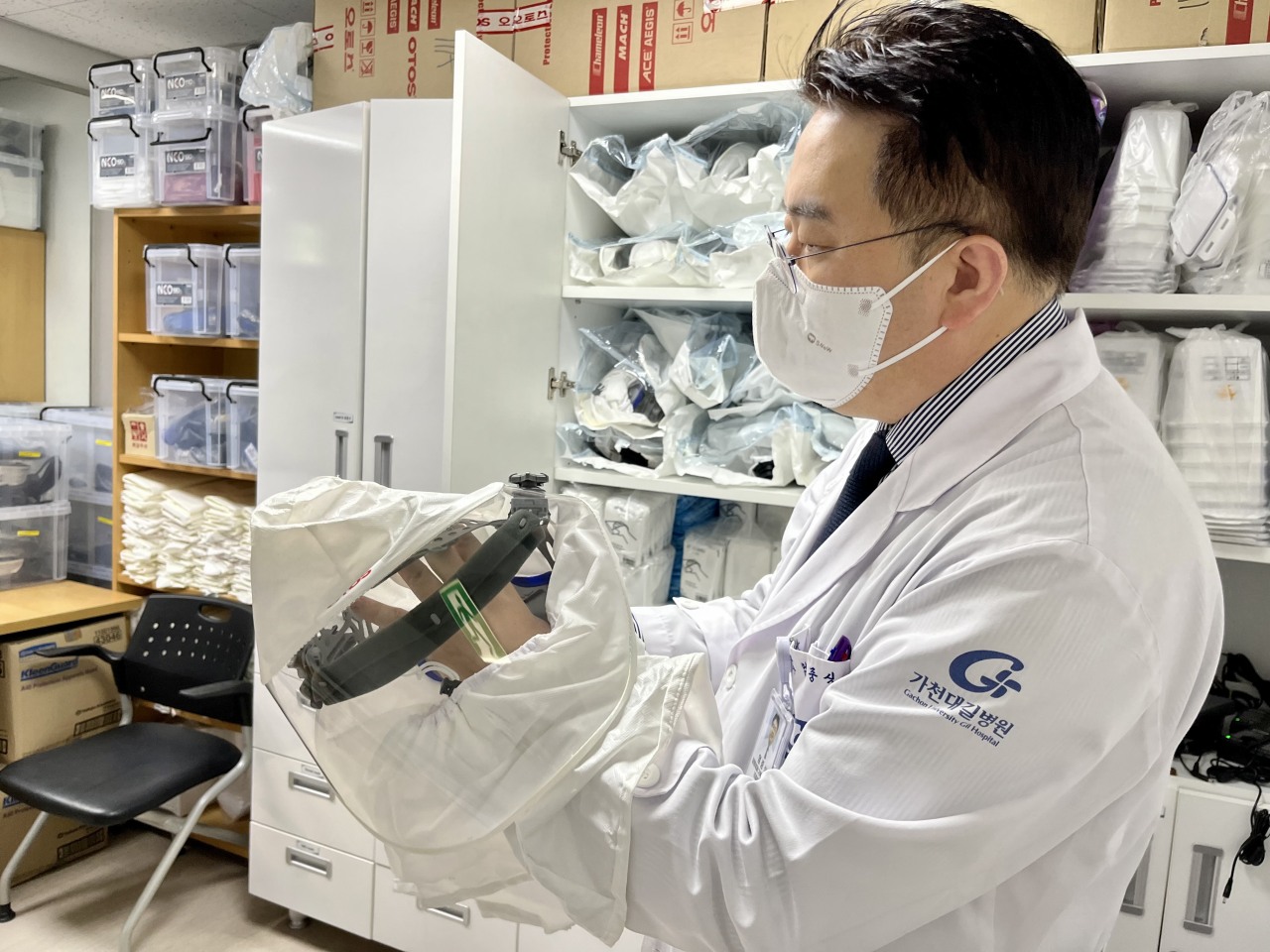

Dr. Eom holds a hood that can connect to hoses that supply air through a battery-powered respiratory called PAPR. PAPR creates a positive pressure inside the face piece, preventing contaminants from flowing in. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

Nurses change into protective suits ahead of their evening shift on Christmas Eve. Dr. Eom, on the right, is seen holding an N95 respirator. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

Here the staffers remove all of the protective gear worn during a shift, to be disposed of as medical waste, before heading to the showers. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

It was only around 3 p.m. and in the changing room nurses were already getting ready for their evening shift. The patient handover could take as long as an hour, they explained. A nurse with a surname Koh, who was fitting a N95 respirator tightly around her nose and mouth, said she wasn’t going home to family for Christmas Eve, Christmas Day or hardly any other holiday, for that matter.

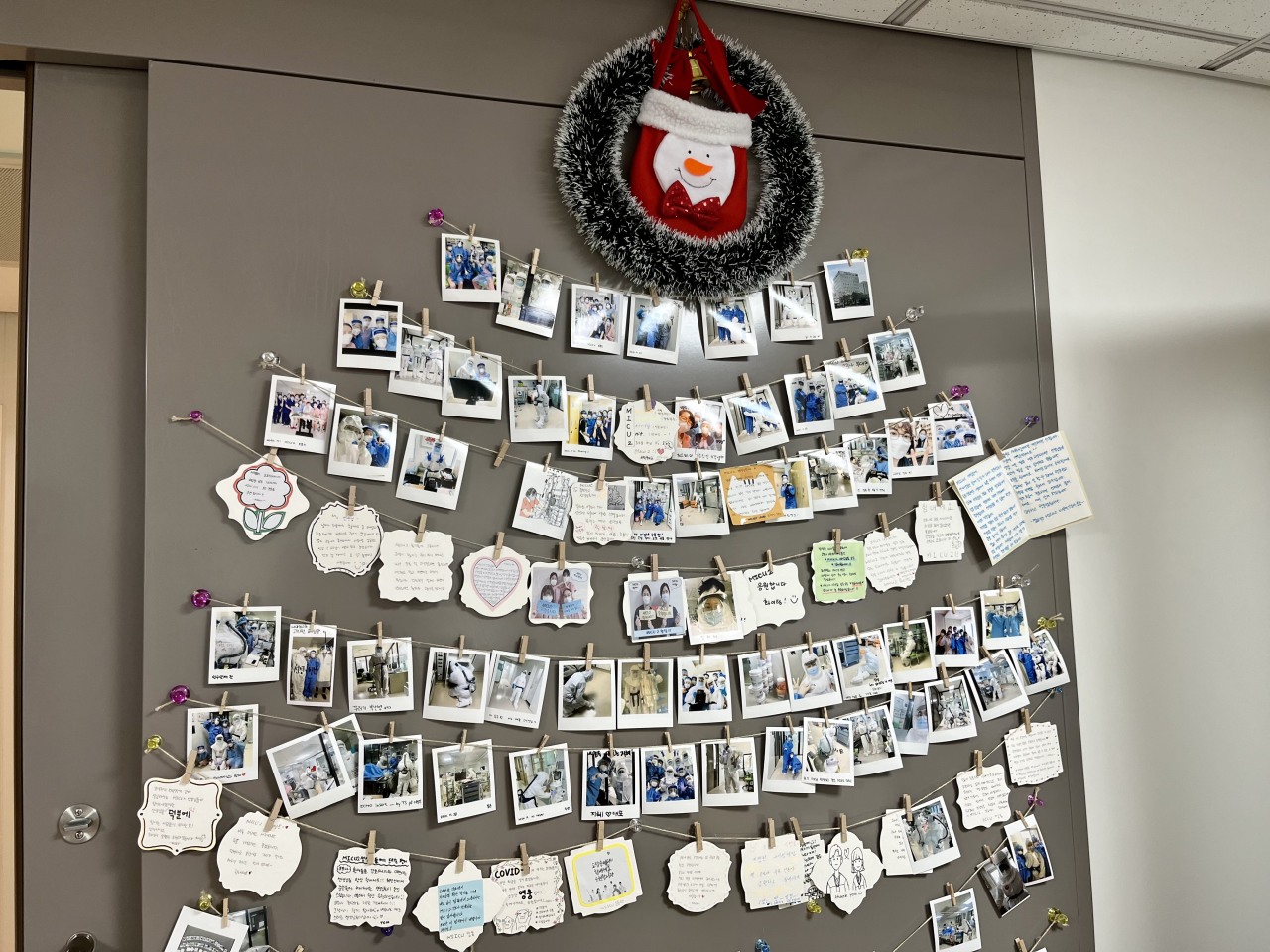

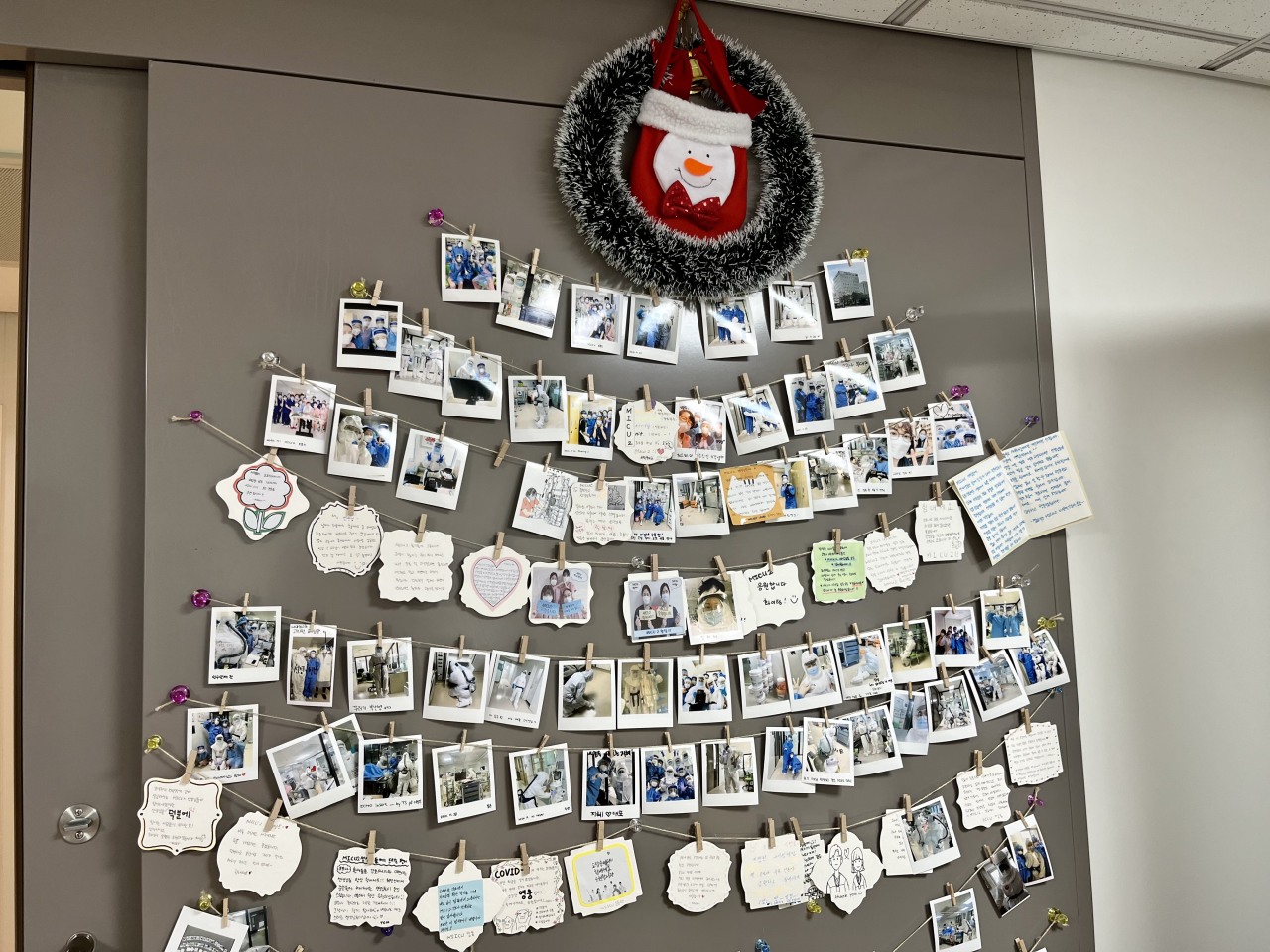

Polaroid photographs of ICU workers and wish cards hanging in the shape of a Christmas tree on one corner of the wall offered the only glimmer of festivity. One of the messages read, “We’re beating COVID-19 one day at a time. Every day we’re closer to the light at the end of the tunnel.” “It’s been an honor working alongside all of you. Though I’m leaving, if you need my help -- call me, and I’ll be there,” read another.

On the other side of the wall, a sign said members of the same team were not to dine together, and that nonessential in-person meetings were strictly barred. This way should one of them get sick, no others would need to go into isolation along. It was a necessary protocol to minimize staff exposure, but one which made the fight lonelier.

Being under layers of protective equipment can get suffocating even after just a few minutes. Each round in the full gear is not meant to last more than two hours at a time to prevent fatigue -- a hospital policy that seldom went observed amid the ever increasing workload.

The powered air-purifying respirator, or PAPR, which comes with a belt-mounted unit weighing a few kilograms and a hose attached to a hood, helps extend that time a bit longer. “But look how heavy this thing is,” Eom said, handing over the gear.

He said about half of the nursing staff at the COVID-19 ICUs have handed in their notices. “They’re staying for the patients until their replacement is hired and trained. Honestly who can blame them?” he said.

More than a year since the hospital was designated to treat COVID-19 patients, no hazard pay or any other form of pandemic pay has come from the government for the staff. “They give just enough to build the extra beds, and even that comes months late,” he said. The aid for August, for instance, just arrived a couple of weeks ago. There was no knowing when the next payment would come.

“I just wish we had been more prepared before restrictions were eased extensively all around the country on Nov. 1 -- a decision that did not involve hospitals on the forefront. We were not told to increase beds or prepare for a surge then, and now we‘re left scrambling trying to make room.”

Eom said he did not think this will be the last Christmas of the pandemic.

“My guess is COVID-19 will still be around next Christmas,” he said. “But hopefully by then new advances in science and technology spare us from the worst, and we’ve learned enough to avoid repeating detrimental mistakes made over the past two years.”

On one the walls of the changing room, polaroid photographs and cards are hung in the shape of a Christmas tree. “So proud of our nursing team looking after severe COVID-19 patients. Thank you all for everything,” read one of the messages. Another read, “Go coronavirus ICU team. We can do this.” (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

Dr. Eom Joong-sik, an infectious disease specialist at Gachon University Medical Center, speaks with The Korea Herald on Friday at his office. (Kim Arin/The Korea Herald)

By Kim Arin (

arin@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)