SEJONG -- In South Korea, the military seized control of state affairs for about three decades from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Though Korea is no longer a dictatorship, if asked whether the country still has a privileged class with an abundance of unchecked power, no doubt most ordinary people would not hesitate to point the finger at prosecutors.

But certain segments of society -- notably prosecutors and right-wing politicians -- would vociferously disagree. They would say the prosecution has carried out its duties fairly and righteously, irrespective of who the targets are and which political party holds power.

Korea is one of only a few countries where the prosecution has the overarching authority both to investigate criminal cases and indict criminal suspects, superseding the roles of other investigative agencies such as the police. Essentially, it has a monopoly over the process of bringing criminals to justice.

Citizens have often asked how prosecutors can be brought to justice if they break the law. Who could carry out an independent investigation? Even if there were grounds to lay charges, their colleagues -- other prosecutors -- could choose not to indict them. It is hard to rule out a scenario where corrupt prosecutors escape justice.

The nation has witnessed cases where prosecutors, having resigned over some malfeasance, went on to open private law offices instead of serving jail terms or being stripped of their law credentials.

More to the point, many citizens question whether the prosecution really is politically neutral, as it is purported to be. Critics have raised the issue of judicial transparency, saying some prosecutors-turned-lawyers maintain shady connections with incumbent prosecutors or judges that can influence the outcome of trials.

Members of several civic groups who support the establishment of a Senior Civil Servant Crime Investigation Unit hold a rally in front of the National Assembly in Yeouido, Seoul, in March. The civic groups say the new body should have the authority both to investigate and indict public officials accused of crimes, including prosecutors. (Yonhap)

Now, as newly appointed Justice Minister Cho Kuk strives to carry out a sweeping prosecution reform initiative in accordance with President Moon Jae-in’s campaign pledge, more and more online commenters say senior prosecutors are struggling to hold onto their privileged status.

Commenters also say right-wing lawmakers, and some news outlets, have been aggressive in highlighting allegations of wrongdoing against Cho while glossing over a real need to reform the prosecution.

Public opinion is also unfavorable toward Cho. Polls have shown that more than half the country believes he is not an appropriate choice for the post, aside from the matter of prosecution reform.

The majority appears skeptical about the ironic situation in which an incumbent justice minister who is pushing for prosecution reform is himself under investigation by the same prosecution he oversees and seeks to reform. He faces allegations that his daughter illicitly gained admission first to a university and later to medical school, and that his wife made dubious investments in private equity funds.

More than 50 percent of survey respondents said Cho should step down, several polls showed.

Nonetheless, surveys also show that the majority believe the structure of the prosecution should be revamped, and that a Senior Civil Servant Crime Investigation Unit is needed as a way to break the monopoly and check prosecutorial power.

If the proposed fast-track bill passes in the National Assembly, this new independent investigative agency will have the authority to investigate and possibly indict prosecutors or other public officials who are implicated in criminal conduct.

In May, a poll conducted by MBC and Korea Research International showed that 70.1 percent of respondents were in favor of the establishment of the Senior Civil Servant Crime Investigation Unit, while only 24.4 percent opposed it.

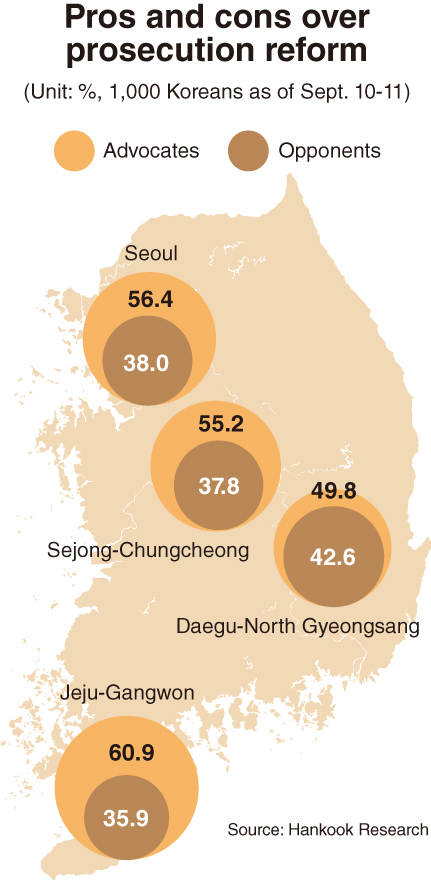

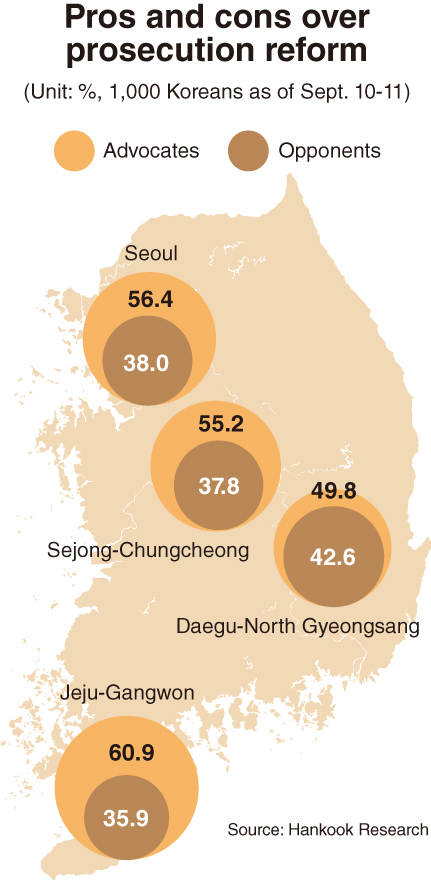

Though support for the bill has declined over the past few months, more than half (57.7 percent) of Koreans supported prosecution reform as of early September, according to a survey from KBS and Hankook Research.

(Graphic by Han Chang-duck/The Korea Herald)

More recently, a political documentary broadcast on KBS reported that 52 percent of respondents to its own survey supported the current prosecution reform plan unveiled by Minister Cho, who took office Sept. 9. Another 35 percent opposed it.

In Busan on Thursday, a group of Korean professors and researchers based at home and abroad released a statement demanding the “urgent reform of the prosecution.” The statement gained support from more than 4,000 signatories, and the group said the country was at a crossroads in the decades-long debate on the redistribution of prosecutorial power and the development of democracy.

Public debate on the need for an independent entity to probe senior officials, including prosecutors, initially came to the fore during the tenure of the Kim Dae-jung administration in the late 1990s.

But the Roh Moo-hyun administration, which took power in 2003, failed to create the envisioned entity despite its strong willingness to do so, due to political conflicts and resistance from senior prosecutors.

The National Assembly predicts that lawmakers will hold a plenary session sometime in the coming months, where they will vote on the fast-track bill to create the independent agency.

While the Justice Ministry is fine-tuning the details of how to revamp the personnel structure in the prosecutor’s office, many netizens share the view that the Assembly should pass the prosecution reform bill, “separately from Cho’s fate” -- that is, regardless of how the ongoing probe turns out for him and his family.

The right-wing Liberty Korea Party opposes the Senior Civil Servant Crime Investigation Unit, predicting adverse effects such as abuses of power by Cheong Wa Dae.

If the fast-track bill faces hurdles before the general election, slated for April 15, 2020, the reform plans cannot but lose momentum, given that the ruling Democratic Party of Korea has lost ground in approval ratings since mid-August in the wake of the Cho Kuk scandal.

One noteworthy question is whether the agency, if it is established, will have the authority to indict prosecutors accused of crimes as well as the right to investigate them.

By Kim Yon-se (kys@heraldcorp.com)