HANAM, Gyeonggi Province -- Prospects of an all-out strike by mail delivery workers of the state-run Korea Post surprised the country last week.

In a nation heavily reliant on fast-speed delivery services, postal workers’ first-ever strike in the 135 year history of the Korea Post would have brought 245 post offices nationwide to a standstill.

Unlike most strikes here that call for a wage hike or an upgrade in employment status, the Korean Postal Workers’ Union urged for a bigger pool of workers and the adaption of a five-day workweek system.

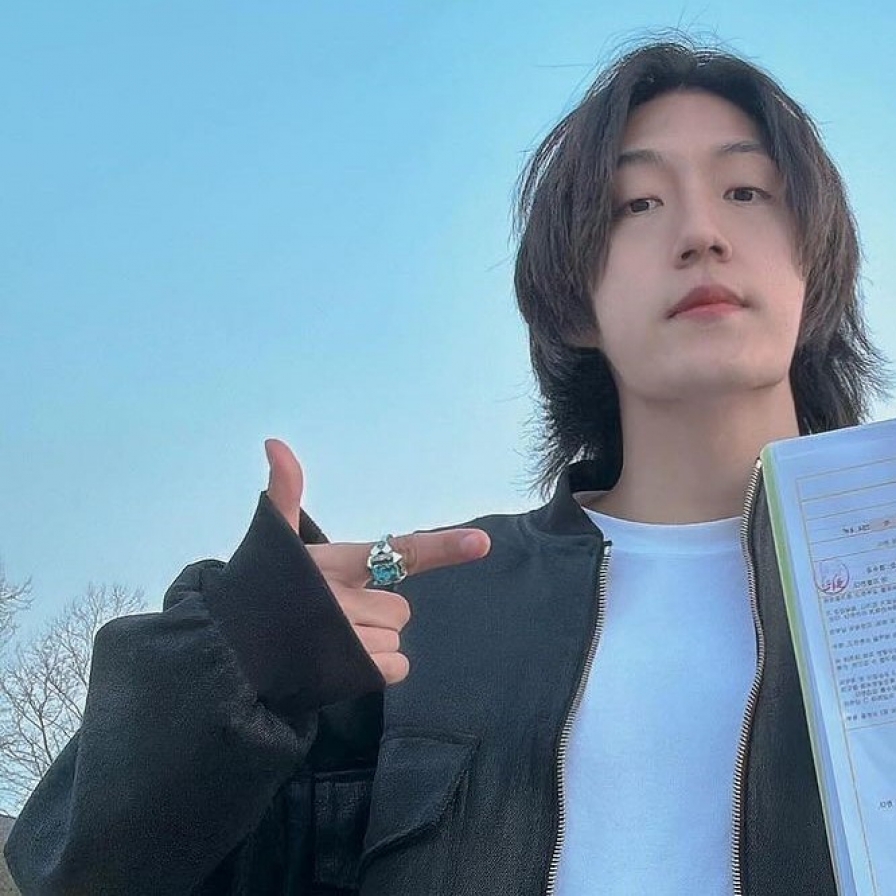

Postal worker Kim Eun-ok of the Hanam Post Office. Kim Bo-gyung/The Korea Herald

Nine mailmen of the Korea Post have lost their lives this year so far largely due to excessive work, according to the union.

It added out of 92 delivery workers who have died in the past five years, 19 are suspected to have succumbed to the work overload.

In a last minute agreement with the government last week, the KPWU dropped its plan for an all-out protest, narrowly avoiding an unprecedented delivery chaos.

But what exactly are the working conditions for some 30,000 postal workers?

“I think I’ll be able to finish deliveries of today’s lot at around 7 p.m. to 8 p.m. … Most of us don’t have time to sit down for lunch, because we have to deliver mail for the area we’re in charge of that day,” postal worker Kim Eun-ok of the Hanam Post Office told The Korea Herald last Friday.

Kim’s day began at 7:30 a.m. sharp at the post office in Deokpung dong, Gyeonggi Province, sorting out mail packages for the region she covers and calling customers to cross-check the time of delivery.

On average she takes off from the post office around 9 a.m. and returns around 6 p.m. But her day does not end for another 1 1/2 hours until she’s done categorizing letters and parcels that could not be handed over to customers.

“The property tax bill came out today, so I have to deliver them in-person and receive customers’ signatures. I’m lucky to have about 200 (bills) to deliver, those who mainly cover apartments have about 500 (bills per person) and those in charge of Wirye (new town) have about 600,” Kim said.

Kim and her team of 13 people have split three areas that should have been allocated to three workers due to the sharp demand hike in postal service in the region with a growing number of new apartments.

The combined number of letters and packages Kim delivers averages some 1,700 per day. With the additional areas her team has to cover, the number of households and offices Kim covers recently rose to about 3,000 units from the initial 2,400.

Swiftly roaming through cluttered streets and uphill roads on her motorcycle, the area Kim is responsible for consists of villas, multiple-family dwellings and low-rise commercial buildings.

“I’ve been working for 15 years and I’ve been on vacation twice. If I’m not here my teammates have to cover my area. ... I’ve never been to one of my children’s graduation ceremonies,” Kim said.

“We are in dire need to more workers,” she added.

Postal workers for the Korea Post, run by the Ministry of Science and ICT, are classified as government workers and should be covered by the 52-hour workweek policy.

In reality, they are obligated to work on Saturdays every other week and the time they spend sorting out mail packages before and after deliveries are not counted as part of their work hours.

Postal workers here work on average of 2,745 hours per year, 982 hours longer than the OECD average of 1,763 hours, industry figures showed.

The numbers were released by a committee consisted of the KPWU, the Korea Post and experts to improve working conditions of postal workers.

The 43-year-old veteran postal worker received shoulder surgery three years ago due to a rotator cuff injury, which is a tear in the muscle that helps raise the arm.

“I came back to work in about a 1 1/2 months before I could heal from the surgery. Someone else on my team also had to go on a sick leave,” Kim said.

As Kim walked up and down the stairs of elevator-less low-rise buildings, in one hand she carried a bundle of packages and bills while calling up customers.

Asked if she has time to use the wash room Kim said “I usually don’t need to go to the washroom in the summer because I sweat (so much).”

The chronic problem of a shortage of postal workers has reached a boiling point with the rapid surge in online shopping here.

South Korea logged its highest-ever online shopping transactions of 11.3 trillion won ($95.8 billion) in late May, according to Statistics Korea.

“In the past the majority of the deliveries were post cards. But now it’s mostly parcels of all sizes that have to be delivered at the doorstep. Recently there has also been a jump in the number of registered mail, which must be transferred in-person. The overall intensity of our work has hugely increased, requiring more energy and time,” Kim said.

The Korea Post’s guidelines for delivery puts the recommended delivery time per letter or postcard at two seconds, registered mail at 28 seconds, and 30 seconds per parcel regardless of the size.

“I started this job as a part-time worker because it gave me a sense of fulfillment. The workload has drastically increased but adjustments in line with the change have not been made,” Kim said.

“I feel despondent. I missed out on my children’s graduation ceremony and I rarely get to take care of the family.”

By Kim Bo-gyung (

lisakim425@heraldcorp.com)