Looking for Mark Tetto’s house in Gaehoe-dong, Seoul, Monday morning, I encounter groups of foreign tourists -- from the Philippines and Vietnam, mostly -- posing and taking pictures against the backdrop of narrow alleys lined with Korea’s traditional hanok. After walking up and down a hill, going round in circles under the blazing morning sun, I finally locate Tetto’s house, its slim gate hard to find between the walls of houses next to it on either side. I swear I had walked past this street 10 minutes ago.

Tetto became a celebrity figure after appearing on popular JTBC talk show “Non Summit,” a show in which foreign panelists discussed a wide range of issues in fluent Korean, and travel program “My Friend’s Home.” He probably had no idea when he first arrived in Seoul eight years ago that he would be where he is today.

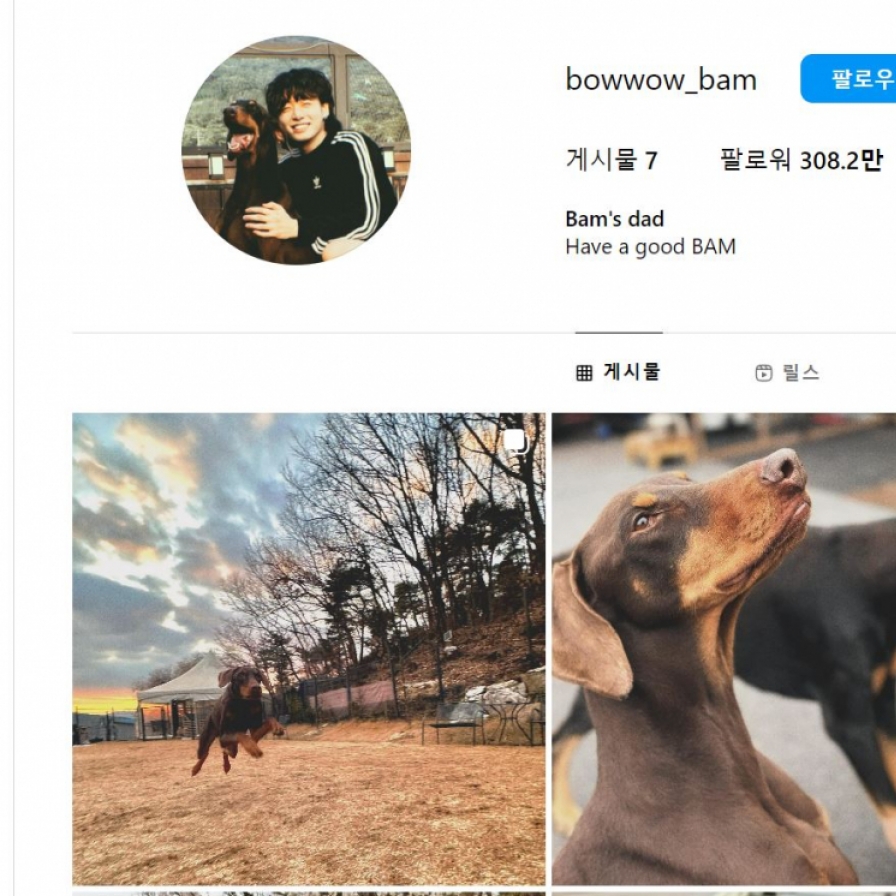

Mark Tetto poses outside his house, Pyeonghaengjae, on Monday. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald)

He came to Seoul in 2010 to join Samsung Electronics’ newly formed mergers and acquisitions team, having previously worked at Morgan Stanley in New York. Today, Tetto is a partner in global investment firm TCK. Most Koreans know him as a TV personality with an Ivy League background. His alma mater is Princeton University and he holds an MBA from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. And that is a good thing, especially in Korea.

While the TV shows have ended now, Tetto’s name continues to pop up, now tied to cultural events and programs -- things that have to do with traditional Korean culture. In January, he made headlines when he was identified as having played a key role in the repatriation of priceless Goryeo kingdom artifacts from Japan, donating them to the National Museum of Korea. Tetto is a member of Young Friends of the Museum, which raised the funds for the purchase of a late 14th century bronze portable shrine, typically used to store Buddha figures, and an 8-centimeter silver-gilt seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from a Japanese dealer.

Tetto has recorded an audio guide for a major exhibition of Korean traditional art and has also interviewed Korea artists and artisans for a local magazine. In April, he was appointed honorary chief gatekeeper at Gyeongbokgung, the first foreign person to be given the honor, according to Tetto.

New house, new life It all began with the house.

When Tetto moved into this hanok three years ago this August, he was plunged into traditional Korean culture and has been on a journey of discovering both traditional and contemporary Korean art ever since.

The story of how Tetto happened to find the house is a reminder that you never know where life will take you, and it will take you on some unexpected turns. His curiosity about hanok was piqued when his friend Nani Park presented him with “Hanok: The Korean House,” published by Tuttle. Park was one of the authors of the book. Before that, he was not familiar with hanok at all. He had been living in an apartment -- also most Seoulites’ housing by default -- in Gangnam for five years.

Pyeonghaengjae (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald)

Tetto took up his friend’s offer to show him around hanok and that was when he first saw what was to be his home.

“It had been renovated in 2004 and was empty at the time,” he says. “The smell was striking,” he says of the scent of wood in the house, and the sound of bamboo leaves rustling in the breeze was intriguing.

I had almost immediately noticed the scent as well, a calming relief from the heat outside, when we sat down for the interview in the kitchen-dining room.

A hanok strikes you visually as well. The windows are proportioned and positioned just so that the scenery outside is captured in a picture-perfect way, the window frames presenting the scene. The kitchen-dining area has windows on three sides, each offering a dramatically different view. On one side, you get a panoramic view of the rest of Gahoe-dong below, an undulating sea of gray-black tiles of hanok. On another side that faces a wall is a still life of an old pine tree complemented by painted Haeju pottery sat casually on the ground. The view opposite the panoramic view of Gahoe-dong is an intimate courtyard with a pine tree and space for a wooden bench.

One striking thing about the interior of this house is the balance between the house and furniture. Having moved in with just a sofa from his old apartment, Tetto went furniture shopping in Nonhyeon-dong but found that the offerings did not fit a hanok. So he turned to sketching designs and having them custom made.

The dining area, small by most apartment standards, does not feel crammed despite the long dining table. The wooden chairs are slim and airy, in harmony with the prevailing mood of the house. The octagonal coffee table in the living room was also his idea, inspired by the lattice design on the sliding door to his study. He had the carpet made to order with the same motif.

“Hanok has become a point of departure to learn about many parts of Korean culture,” he says. “I had no idea about this culture until I moved in. You learn or study it because it is interesting and it is there.”

To find what would suit the house, he studied old furniture. Then he became interested in decorating, which led him to study porcelain, he explains. “Just living here made me learn different parts of Korean culture.”

There has been a definite change in his lifestyle since he moved into a hanok, in addition to all the cultural learning. “Your mindset changes,” he says. “It slows you down and it is healing,” he adds, observing that space can have profound impact on a person.

Another change is that he finds himself spending more time at home. “Living in a Gangnam apartment, I did not like being there by myself and was always out.” In the Gahoe-dong house, it is the opposite. “Saturday morning, sitting out here, it is healing. The house is healing, just sitting here,” he says. “When it rains, it is even more atmospheric.”

Living in hanok has also had a slowing-down effect on Tetto. “Here, it is not possible to just shut the door behind you as you leave the house in the morning. To leave, I need to turn the knobs on the windows,” he says, demonstrating as he closes the windows. “It makes me spend five minutes in the morning collecting my thoughts. It calms me for the day,” he says, breaking into Korean to convey his exact meaning and feeling.

It is not only traditional art that interests Tetto. “I became interested in hanji,” he adds, pointing to the window lattice covered in traditional handmade paper. “I then became interested in modern art made with hanji, as contemporary artists take inspiration from the past. Then I started collecting contemporary Korean art,” he says. In fact, I had noticed a work by Kang Ik-joong, a collection of little squares with paintings of moon jars. “That just arrived home and I am still looking for a place for it,” he says.

The rest of his house is an interesting juxtaposition of new and old. In his study, a contemporary painting hangs above a Joseon era cabinet with drawers. On top of the cabinet sits a Silla Kingdom vessel with geometric patterns and a Joseon box for holding seals. From inside a cabinet drawer, Tetto takes out a sumaksae -- a round tile with relief decorations used at the end of roof tile to close it off. It is one of many sumaksae he has collected, including a set of 20 pieces he bought from a US collector. “I want to donate them to the National Museum,” says Tetto, adding they are thought to be from the Three Kingdoms period but that it must be verified. A geomungo -- considered a gentleman’s instrument -- stands in a corner of the study, as he is studying the instrument.

Like many hanok renovated after 2000, Tetto’s house has a basement, which he uses as private quarters. At the foot of his bed is a folding screen of photos of Joseon baekja, or white porcelain, by photographer Koo Bon-chang. In the guest room, a large photograph of a palace garden seen through a window printed on hanji has the effect of opening up the small room.

As we walk toward the main gate at the end of the house tour, Tetto points to greenery on either side of the narrow path. He has been planting what would have normally been found in traditional Korean gardens, with the help of a landscape artist who specializes in the field.

Opening the main gate, we hear the noise of the outside world -- tourists and all. It is amazing how you don’t hear any of this behind the doors, Tetto notes. Wondrous indeed, I think to myself, as I leave the cool oasis of Tetto’s hanok, and head back to the real world in blazing heat.

By Kim Hoo-ran (

khooran@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=645&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)